So, you’re heading to Paris, and you’re only going to visit one museum. It’s going to be the Louvre, right?

Let me change your mind! If you love 19th-century art, your first priority should be visiting the Musée d’Orsay.

It’s only a short distance to the Louvre, one of the world's largest and most famous museums.

- Tickets and Hours

- Rise of Impressionism

- Rebal Artists of 19th Century Paris

- Sordid Tales of Post Impressionism's Wild Men

However, it’s filled with a well-curated collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art that will make your jaw drop, your eyes well up, and your brain swirl with possibility.

Here are just a few of the famous themes and artists you’ll witness in the Musée d’Orsay:

- Edgar Degas’ ballerinas

- Claude Monet’s water lilies

- Mary Cassatt’s female subjects

- Henri de Toulouse Lautrec’s chaotic nightlife

- Édouard Manet’s scandalous nudes

- Jean-François Millet’s pastoral bliss

- Gustave Courbet’s shocking realism

- Berthe Morisot’s domestic magic

- Vincent Van Gogh’s madness

- Paul Gauguin’s exploitation of innocence

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Parisian pastimes

- And so, so much more!

You could spend days – even weeks – in the Musée d’Orsay, so I’ve narrowed down just a few to highlight.

The History of the Musée d’Orsay

The history of this structure dates to 1810 as a government palace.

But in 1871 it was set alight by a rioting mob and sat derelict until 1899 when it was repurposed and rebuilt as a grand train station.

By 1939, the station was outdated, and it once again sat empty for decades.

It was scheduled for demolition in the ‘70s, but people were outraged by this idea, and the idea of a new art museum gained popularity. The Louvre was packed with artwork, a lot of it in storage.

So, the Louvre suggested that they relocate their collection from the second half of the 19th century and the rise of Impressionism into a dedicated new art museum.

And the Musée D’Orsay, located here at the Quay d’Orsay, was fully renovated and opened here in 1986.

Hours and Ticket Prices

The Musée d’Orsay is open 6 days a week, from Tuesday to Sunday. Its normal hours are from 9:30am-6:00pm, except on Thursdays when it is open until 9:45pm.

Full-price tickets are €11. A reduced rate of €8.50 is available for 18–25-year-olds, and the museum is free to anyone under 18, or any EU citizen between 18-25.

For a few euros more, you can buy your ticket online which allows you to enter through the reserved entrance, skipping the line.

If you’re going during the summer, this can easily be worth two extra euros.

As with many museums, the Musée d’Orsay can be overwhelming. There are tours and audio guides offered by the museum for €6 and €5 respectively.

The guided tours are for adults, and children under the age of 13 are not allowed on them.

However, you can also go on a guided tour from an external company, such as Get Your Guide.

They offer a lot of ‘skip-the-line’ guided tours that will walk you through the history of Impressionism and help you understand the complexities of this museum.

Of course, you can also watch the videos linked here to help you plan your visit to the museum.

Across three informative videos, Jessica the Museum Guide (that’s me!) shows you the history of this fascinating place.

I lead you through a comprehensive self-guided tour of the Musée d’Orsay, which you can follow below.

Part 1: The Pre-Impressionists

Part 2: The Impressionists

Part 3: The Post-Impressionists

Getting to the Musée d'Orsay

The museum’s address is: 1 rue de la Légion d'Honneur, Paris 75007.

The easiest way to get there is by Metro, either station Solferino on Line 12 or the station Musée d’Orsay on the RER C.

It is also very central, just across from the Louvre if you would like to walk.

Self-Guided Tour of the Musée d'Orsay – Pre-Impressionism

We’ll start our tour with the Pre-Impressionists, who you will mostly find on the ground floor.

This part of the tour corresponds with this video, if you want to prepare in advance.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – La Source

Ingres was one of the most important ‘academic painters’ – that is, he adhered strictly to the rules of style and subject matter set out by the Parisian Salon system.

To be considered a successful artist in Europe, your paintings had to follow these rules.

The art had to be realistic, high-minded, and only depict the “correct” subjects, such as mythology, great battles, and idealised portraits.

No brush strokes should be visible, and each painting should be ‘perfect.’

Ingres exemplified this style. After all, he was the president of the École des Beaux-Arts! He worked on this painting for 40 years, and it was a hit.

The subject represents both virginity and fertility - framed by ivy, a symbol of Dionysus, the god of disorder, regeneration, and ecstasy.

Eugéne Delacroix – Preparatory Sketches for The Lion Hunt

In 1854, the Director of the Fine Arts department at Musée de Bordeaux asked Eugéne Delacroix to create "a painting, first submitting the subject and the sketch to me for approval."

Delacroix was already revered and famous for his controversial 1830 painting “Liberty Leading the People.”

He chose to depict the riotous Lion Hunt, inspired by engravings after Rubens' paintings The Hunts.

This is a sketch for that painting, which was damaged in a fire at the Musée de Bordeaux in 1870.

While the elements of the Lion Hunt are hard to see, you can make out the rearing horse in the centre and the wild chaos of colours - yellow, blue, and red.

The critics hated the painting and this study – this went against everything the Academy stood for! But it was deeply influential.

Jean-François Millet - The Gleaners (1857)

Jean-François Millet was a French painter renowned for his paintings of peasants.

He helped found the Barbizon school in rural France, which was all about pastoral scenes and landscapes.

Millet studied the work of gleaners for ten years before tackling this painting.

Remember - though we see these subjects as pastoral bliss, this was a very unusual and even controversial subject matter.

The Paris salons were all about idealised beauty or heroic wars.

But instead, Millet focuses on peasant life, and showing their back-breaking labour as they pick ears of corn missed by the harvester.

Social class is very much on display without portraying an exploitative or over-the-top view of poverty. This is realism without idealism.

Gustave Courbet - A Burial at Ornans (1849–50)

"When I stop being controversial, I'll stop being important.” – Gustave Courbet

This painting rocked the art world - it has been described as “upstart in dirty boots crashing a genteel party.”

It’s called A Burial at Ornans and includes more than forty human-sized people, almost all of them in black.

We encounter them as we walk through the Musée D’Orsay, and it’s almost like we’re attending the funeral.

Courbet is purposely breaking the rules of French painting at the time - a canvas this large should depict historical events or gods in an idealised light.

Proper artists used models, not the ordinary people – including the gravedigger - at a funeral.

No matter what, here Courbet shows us - and the Salon - that even provincial labourers like the gravedigger were worthy subjects for art.

Édouard Manet - Olympia (1863)

Now for my favourite painting in the Musée D’Orsay!

Édouard Manet believed in a radical rejection of traditional subject matter, and he was lambasted by the Paris Salon Crowd.

Olympia shook French painting to its core, and it continues to influence us to this day.

It was displayed at the 1865 Paris Salon, where it caused a complete uproar.

Not because of the woman’s nudity - I mean, we already saw La Source, but because of her bold stare and direct eye contact.

The nude woman was interpreted as a sex worker in her brothel.

She is modelled by Victorine Meurent, who later became an accomplished painter in her own right but could never shake the scandal associated with this painting.

This painting became so notorious that the name Olympia was associated with all sex workers in 1860s Paris.

Laure’s servant reminds us of the racial stereotypes common in 19th century France - at the time this was painted, slavery had only been abolished in France 15 years earlier.

Claude Monet - Women in the Garden (1867)

We’ll talk at length about Monet when we head upstairs, but for now, let’s have a look at a piece from 1866 - early in his career, when he was just 26.

Women in the Garden is a large canvas painted ‘en plein air’ - that is, outdoors. Camille Doncieux, his future wife, posed for the figures.

Monet was experimenting with method and subject matter. This piece was rejected from the Salon in 1867 because of its narrative weakness.

Remember, Salon paintings were meant to be monumental and grand.

The Salon judges also told him that his heavy brushstrokes were a problem - which would, of course, go on to become his hallmark.

This piece isn’t quite Impressionism - but we can see many of the elements starting to take shape. We will meet Monet again upstairs.

Self-Guided Tour of the Musée d'Orsay – The Impressionists

After covering the ground level, head straight up to the 5th floor. This is the home of the Impressionists.

You’ll also notice that there are two great viewpoints: one immediately to the left of the escalators, looking over the floor of the museum, and one straight on, giving an amazing view of the city of Paris towards Montmartre and the Basilica of the Sacré-Coeur.

In many ways, the Impressionists were an odd group. They were drawn together more by their distaste for the old system than a shared passion.

As a result, there is a lot of variation in their paintings, but one thing you’ll notice is that they are all very intentional with their treatment of light.

It has famously been said that their subjects were not the objects in the paintings, but the way the light acted around the objects.

This next section of the tour corresponds to this video, exploring the Impressionists.

Henri Toulouse Lautrec - Dance at the Moulin Rouge (1895)

We’re upstairs now and about to start the journey of Impressionism. However, before we do, we’re jumping to a post-Impressionist piece by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

I’m not sure why the curators decided to place him here, but it could be because we are looking out over Paris through the clock faces, and he is such a quintessentially Parisian character.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is known for his debauched lifestyle, almost as much as he is known for his art! He called his scenes “nocturnal paradises.”

In this painting, the star of the show is infamous dancer known for her frenetic can-can - Louise Webber, or La Goulue (the Glutton), because of her love of the drink.

She’s with her partner, "No-Bones" Valentin.

Even in a crowd scene like this one, everyone is highly individualised. And look - we can see Toulouse-Lautrec himself!

Édouard Manet - Le Déjeuner sur L'herbe (1862)

This is Manet’s most famous piece, called Luncheon on the Grass (Dejeuner sur l'Herbe) painted in 1862.

While the Academy did accept Olympia for a Salon, they rejected this piece.

The juxtaposition of the naked women and the clothed bourgeois men was simply too shocking and evocative of sex work - the academy was scandalised.

Again, with this work, Manet is paying homage to Titian and a painting called The Pastoral Concert. Being rejected from the Paris Salon didn’t discourage our man Manet!

Instead, he displayed this painting at an alternative Salon called Le Salon des Refuses - the Exhibit of the Rejects.

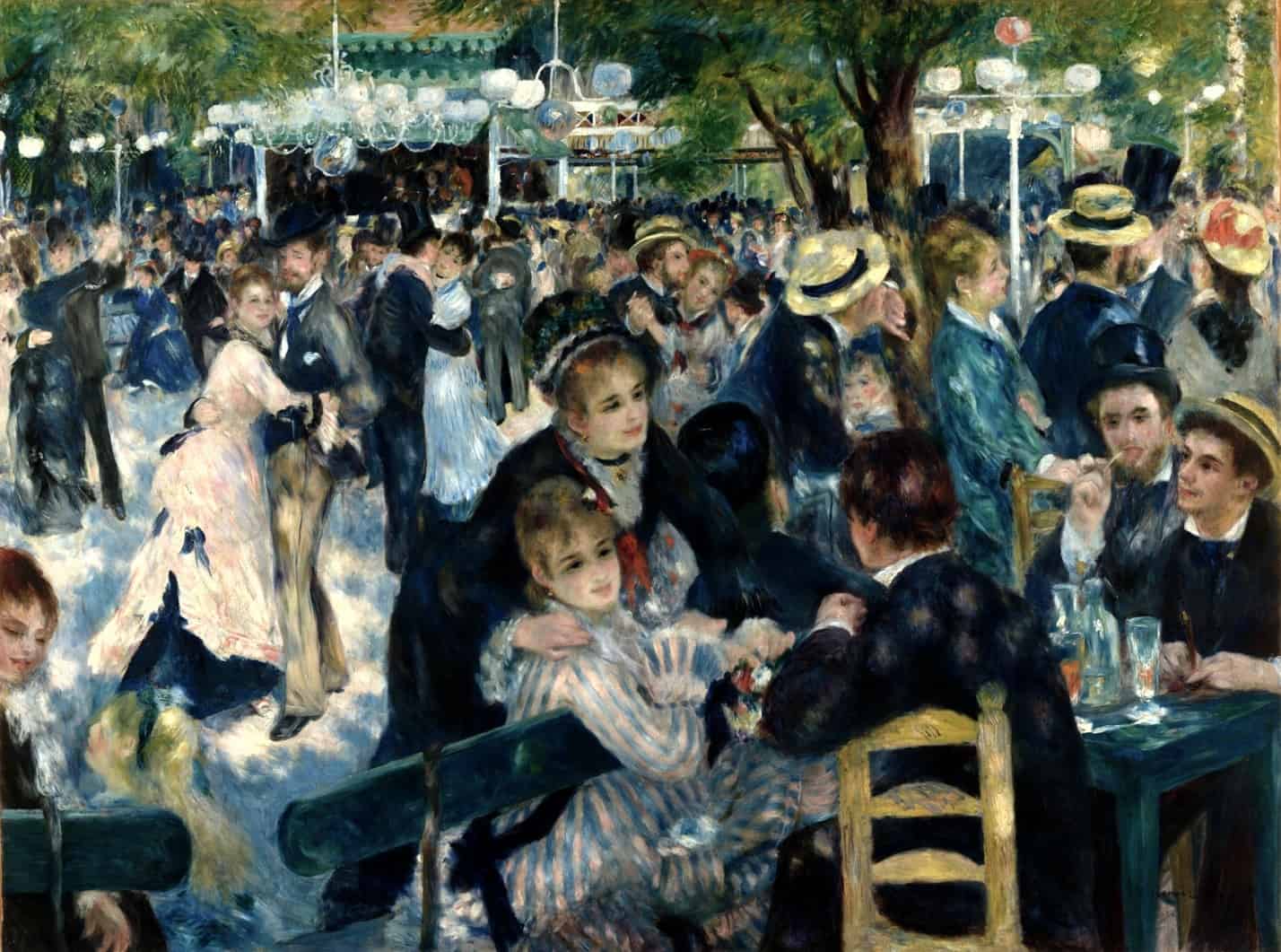

Pierre Auguste Renoir - The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette (1876)

Now we meet Pierre-Auguste Renoir, one of the impressionists who loved to paint en plein air - that is, outdoors.

His paintings, like this delightful one, are defined by their loose brushwork and bright, cheerful colours.

It gives us a glimpse into the world of France's Belle Époque, a time period of peace and prosperity in France, usually dated between 1870 and the outbreak of WWI in 1914.

The setting is an outdoor beer garden called the Moulin de la Galette.

When Renoir painted this in 1876, Impressionism was still in its infancy - he, Degas, Monet, and Pissarro had just held the first Impressionist exhibit 2 years earlier.

He is known for his gauzy brushwork and vivid colours - you can really see this in this painting.

Edgar Degas – The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer (1880)

Before Impressionism, ballerinas would have always been painted in an idealised way, with only their feminine grace and flawless beauty on display.

However, Degas knew that the dancers were serious athletes, and he paints and sculpts them as such.

This 1880 sculpture, called The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer (La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans) depicts a Belgian girl called Marie van Goethem.

You’ll see ballerina sculptures like this in museums around the world - there are 28 bronze versions.

Though we might think of ballet as a middle-class endeavour, the so-called Petit Rats, or little rats, of the Paris Opera were often poor and dressed in shabby hand-me-downs.

Dancers had always been portrayed as graceful and ethereal, but here, the dancer is realistic and tense.

According to art historian Tim Marlow, her face is "contorted, people thought it was a deliberate image of ugliness.

But, you could also say it's the image of a sickly gawky adolescent who is being made to do something she doesn't totally want to do."

Mary Cassatt - Young Woman Sewing in the Garden (1882)

This painting is by Mary Cassatt - one of the few successful female artists of the time, along with Berthe Morisot.

She was from a wealthy Pennsylvania family, and came to Paris in 1865 to study painting. This was quite difficult for her, as her father once said he would rather see her dead than an artist!

She took on some of the influences and techniques of Impressionism, but she developed her own style and began to investigate scenes that her male counterparts ignored.

She was particularly interested in the contemporary lives of middle-class women.

She depicts sewing, reading, and writing letters, and she is known for her sensitive and nuanced paintings of women and their children.

However, in this painting, she depicts a young woman seated in a garden. You can see the broad, impressionistic brushstrokes and rich colours that are hallmarks of Impressionism.

Camille Pissarro - Les Coteaux du Vesinet (1871)

Often called the father of impressionism, Pissarro, of French and Danish descent, Pissaro was born on the island of St Thomas.

He was a student of Gustave Courbet and later became the "dean of the Impressionist painters" - because he was the oldest of the group and "by virtue of his wisdom and his balanced, kind, and warm-hearted personality."

Along with the other Impressionists, he believed strongly in portraying the realism of a scene, and in showing individuals in natural settings - he despised grandeur and artifice.

Berthe Morisot - The Cradle (1872)

Morisot completed this painting in Paris in 1872, depicting her sister Edma watching over her baby daughter Blanche. This is a deeply intimate painting again showing us into the world of women in the 19th century.

This painting was shown at the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874 - she was the first woman to show with the group.

It was hardly remarked upon, although a few critics did point out its grace and beauty.

It did not sell, and it remained with the Morisot family until the Louvre purchased it in 1930.

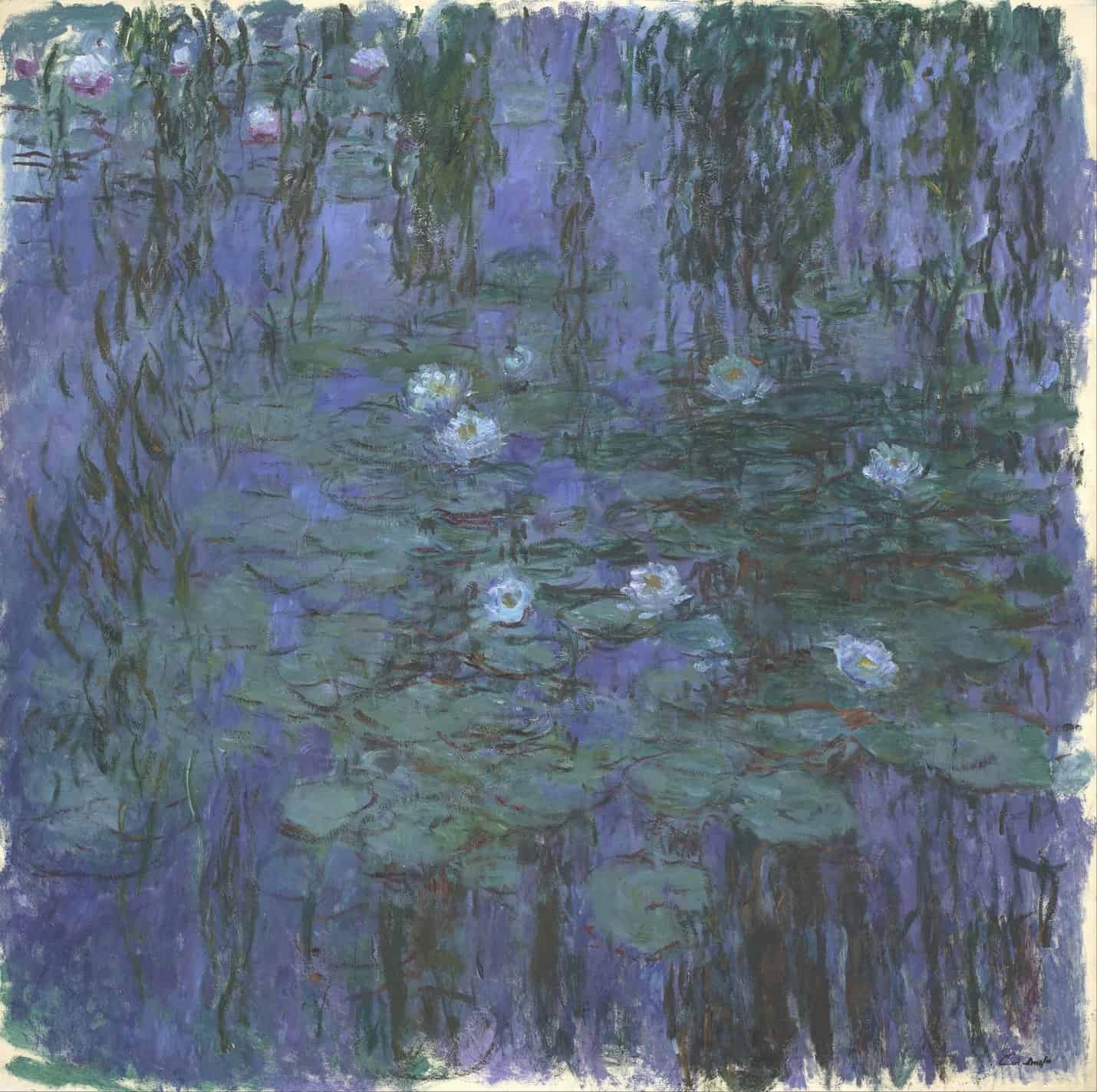

Monet - Blue Water Lilies (1916)

We’ve talked about Monet quite a bit, and we’ve seen one of his pre-Impressionist works, the Women in the Garden.

But, now let’s move on to one of his most iconic pieces, Blue Water Lilies, one of 250 paintings of lilies in his water gardens.

This was painted between 1916 - 1919, when he had already been painting water lilies in Giverny, Normandy for nearly 40 years. This was the bulk of his career!

According to Monet, “It took me some time to understand my waterlilies. It takes more than a day to get under your skin.

And then all at once, I had the revelation – how wonderful my pond was – and reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.”

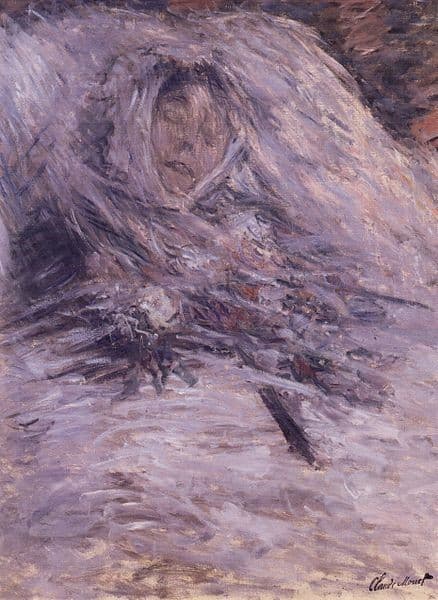

Monet - Camille Monet on Her Death Bed (1879)

But now, let’s head to our third and final Monet piece, painted much earlier in his life.

We see a much darker subject matter - his beloved wife in the moments after she passed away.

The painting is called Camille Monet on Her Death Bed, or 'Camille Monet sur son lit mort.”

While we associate death with dark colours, Monet is painting her in the final moments of her life and first moments of death - using gentle shades of white, pink, and blue.

Camille, who died of a terminal illness, perhaps cancer, in 1879, is shrouded in a veil.

As his beloved wife took her dying breaths, he later said, “'I found myself staring at the tragic countenance, trying to identify the shades in the colour, the proportion of light and the sequence.'

He noticed the soft blue, yellow, and grey, and he recalled, 'the thought occurred to me to memorise the face that had meant so much to me.'

Self-Guided Tour of the Musée d'Orsay - The Post-Impressionists

Now, let’s move on from the Impressionists to some artists who straddled the boundaries between Impressionism and what would come next.

Cezanne – Kitchen Table (Still Life with Basket) (1888 – 1890)

Painted between 1888 - 1890, Kitchen Table (Still-life with basket) is an intricate composition - every detail is carefully calculated.

Look at the way that the pots, fruits, a basket, and cloth are all carefully assembled on a kitchen table.

No detail has been spared - however, the table is tilted, and some of the pots look unstable on the surface.

Look at the grey pot and the basket - they have no more surface left on the tabletop.

Cézanne wanted to represent a more profound truth that could be presented in painting but not in reality.

He would go on to paint more than 200 still lifes during the later stages of his career. He said, “I shall astonish Paris with an apple.”

Georges Seurat - Le Cirque (1890)

Now here’s a painting that will make you smile. It’s called Le Cirque - or the Circus, and it’s by

Georges Seurat. In fact, it’s his final painting, done in a Neo-Impressionist style in 1890–91.

This was his third work about the Circus, showing us a female performer standing atop a horse at the Circus Fernando.

This work is an example of Divisionism, where small dots of bright colour create shapes and images - he makes use of a technique called pointillism here, which uses tiny dots to create pictures.

Vincent Van Gogh - Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888)

Here we have a piece by one of the most famous painters of the 19th century - Van Gogh’s piece, commonly known as Starry Night Over the Rhône.

Let’s just start by saying that Van Gogh, though inspired by the Impressionists and their use of light and their loose brushstrokes, is often considered a post-Impressionist painter.

Of course, Van Gogh is now one of the most famous painters in the world, but that was not the case when he was alive.

In fact, he was not even a painter until the age of 30, and his career in this field was incredibly short - he died at age 37.

Van Gogh moved to the Arles in the south of France in 1888, and he was incredibly inspired by vivid colours of the countryside. Sadly, this is also where his mental health suffered.

Like Monet, Van Gogh was obsessed with colour, and the new artificial lighting was fascinating to him.

In this painting, he captures the reflections of the town’s gas lighting as it hits the dark night water of the Rhône.

You can also see two lovers strolling by the banks of the river in the foreground of the painting.

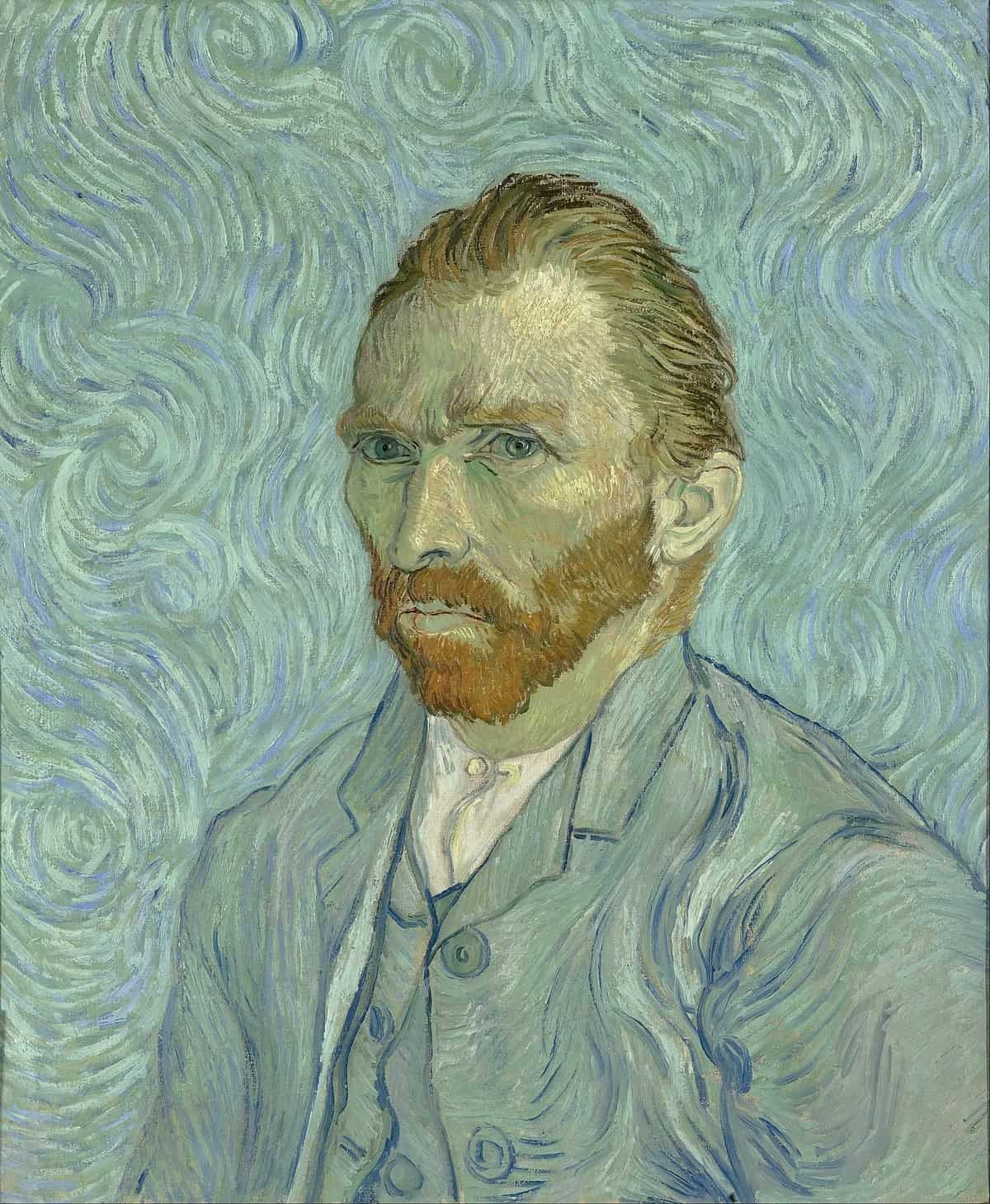

Vincent Van Gogh - Portrait of the Artist (1889)

Here is our second piece by the famous Dutch post-Impressionist.

This is a self-portrait of, which he painted in oil on canvas in 1889. This could be Van Gogh’s final self-portrait of the 32 he produced over 10 years.

We’ve seen a lot of artist models today - but Van Gogh lacked the money to pay for them, so he often used himself.

Most art historians think he painted this work just before he left the mental asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence and brought it with him to Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris.

Just a few months later, he would take his own life, a tragic end to his far too short story.

Paul Gauguin – Arearea (1893)

Let me preface this section on Paul Gauguin by saying that Gauguin was not a good person. sIn his own words, he was an infidel,’ a ‘monster,’ ‘a savage, a wolf in the woods without a collar.’

He fled Europe for a more “exotic and primitive” life where he could be free from money - and also from his wife and children.

When he arrived in Tahiti when he was 43, Gauguin preyed on young Polynesian girls and had sexual relationships with girls as young as 12 and 13.

This piece, titled Arearea, was displayed at his 1893 exhibition. This painting was not received well by critics, and the red dog was heavily mocked.

However, it was one of Gauguin’s favourite paintings, and he bought it back in 1895 before he left Europe for good.

That’s the end of our tour, but of course, there are hundreds of other paintings and sculptures to enjoy.

Take your time to enjoy the sculptures and ambience as you leave the museum, and be sure to watch the videos to learn even more.

Jessica O’Neill is a long-time London guide with Free Tours by Foot, and she’s also known as The Museum Guide.

Check out her museum tours on YouTube, and feel free to ask her questions about hotels on our London Travel Tips Facebook Group. She also helps plan London itineraries for tourists, so do get in touch.

She loves craft beer, great food, strange oddities, and petting your dog.