When stepping into San Francisco’s Chinatown, you step into a world of vibrant colors, sounds, sights, and smells that will immediately whisk you around the globe. While there are several distinct Chinese neighborhoods in San Francisco, the oldest and largest Chinatown lies in the heart of downtown. On this tour, you’ll visit sights with history dating back to the days of the early explorers, see unique and beautiful views of the city, and be immersed in a culture so intertwined in San Francisco’s history that you just can’t miss it!

Since we are not offering our Chinatown/North Beach tour currently, please use this self-guided tour of San Francisco Chinatown for some fun stories as you visit this neighborhood.

For more money saving ideas for your time in San Francisco, check out which tourist discount pass is best.

You can also download San Francisco Chinatown Self Guided Tour as a pdf.

One of the largest concentrated Chinese populations outside of China, San Francisco’s Chinatown is the oldest in North America and the largest outside of mainland China. The earliest Chinese immigrants to the Bay Area came in the 1840s, just before the Gold Rush. Some of those early Chinese immigrants began referring to San Francisco as “Gold Mountain,” and, just as fortune seekers hurried west across the country to hunt gold, so too did Chinese immigrants come into the Bay seeking new lives. As one of the most accessible mainland North American ports, San Francisco’s Chinese population grew steadily to become what it is today. Now, as you walk through the hustle and bustle of Chinatown, you’ll feel as if you’d stepped off a plane and landed in Hong Kong. If it weren’t for the towering Transamerica Building to the east or views of Coit Tower farther north, you might forget that you’re in San Francisco at all.

While taking this tour, be sure to take some time to look in the many different shops along the way. We’d run out of space if we tried to list them all, but you can find practically anything in Chinatown.

We begin this walking tour at the iconic Chinatown Dragon Gate, the entry to Chinatown, and complete it farther north along Grant Ave., where Chinatown and North Beach intersect.

Heads up: This being San Francisco, you will have a few hills to climb. Don’t be too concerned, most uphill sections are fairly short or broken up with stops.

Begin the tour at the Dragon Gate, located at the intersection of Grant Ave. and Bush St.

Stop A. Dragon Gate (1970)

One of the most photographed sights in San Francisco, the Dragon Gate officially marks your entrance into Chinatown. Though the Chinese community began creating Chinatown as we know it in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake, the official entrance to the neighborhood wasn’t marked until 1970. Chinatown representatives eagerly pushed for a ceremonial archway, a common entrance to most Chinese villages, in order to show how similar San Francisco’s Chinatown was to a traditional Chinese village. Designed by Clayton Lee, a Chinese American architect, the Dragon Gate is one of the most spectacular and authentic in any American Chinatown. Built mainly in Taiwan and covered in beautiful Taiwanese tiles, the Dragon Gate stands as a beacon welcoming visitors under its archways. Be wary of which archway you pass under, though! The two side passageways are for the common people, while the larger center passage is reserved for esteemed dignitaries and important citizens… and delivery trucks. As you walk past the Dragon Gate, check out the dragons standing guard on each side - it’s said that they’re busy keeping evil spirits out.

Walk up Grant Ave. for one block. As you walk, peek into some of the shops along the way. Though most are souvenir shops for tourists, you never know what fun things you might find. When you reach the intersection of Grant Ave. and Pine St., cross Pine and make an immediate right. As you begin descending Pine, you will see the entrance to St. Mary’s Square on your left. Enter St. Mary’s Square.

Stop B. St. Mary’s Square

This may be one of the calmest locations in Chinatown, so relish it while you can. Occasionally occupied by tai chi groups, St. Mary’s Square is prime real estate that’s very existence is continually in question. Located on the fringes of both Chinatown and the Financial District, it is not as busy as Portsmouth Square (a later stop). Various businesses have attempted to purchase the land for office buildings, but recent rebuffs from Chinese cultural groups almost ensure that it will remain an open green space. Though the area is fairly calm now, during San Francisco’s rough and tumble Gold Rush days, the square housed some of San Francisco’s most notorious houses of prostitution. The area changed drastically in 1906 when the houses were destroyed in the fires caused by the great earthquake. Following their destruction, city officials decided to put a park in their place. The park is named for Old St. Mary’s Cathedral, located across California St.

After walking into St. Mary’s Square, head toward the center where you’ll see what looks like a small fence. On that is the San Francisco Chinese American War Memorial.

Stop C. San Francisco Chinese American War Memorial

In St. Mary’s Square, you will see two important memorials. First, on metal fence near the center of the square is the San Francisco Chinese American War Memorial plaque dedicated to those Chinese Americans who served and gave their lives for the United States during World Wars I and II. The plaque lists the names of those killed and shows the emblems of the different branches of the military represented by Chinese Americans. The American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars seals are at the bottom of the plaque.

Also in the square is a statue of Sun Yat-sen. Head toward that and read on.

Stop D. Statue of Sun Yat-sen

The other memorial in St. Mary’s Square is a Benny Bufano statue of Sun Yat-sen, erected in 1937. Sun, an exiled anti-imperialist known to many as the “Father of Modern China,” worked fervently through the early 1900s to overthrow the Qing dynasty, only to see his efforts rewarded with exile from his home country. He came to San Francisco and, it is said, often relaxed in St. Mary’s Square. Unfortunately, his life in San Francisco was not completely restful; agents of the Qing dynasty were constantly searching for him, and he was often in hiding. Sun Yat-sen’s famous words, “The world is for all, all is for the people,” are inscribed in traditional Chinese characters on the Chinatown Dragon Gate. Benny Bufano, the sculptor of Sun’s statue, was born in Italy but lived in San Francisco for much of his life. His works can be seen throughout the city.

Walk out of St. Mary’s Square on the side opposite of that which you came in. You will exit onto California St. Look in front of you for an iconic San Francisco landmark.

Stop E. California St. Cable Car Line

The cable car is one of San Francisco’s most iconic sights, and the California St. line is the oldest cable car line in the country. The San Francisco cable car, invented by Andrew Hallidie in 1873, became one of San Francisco’s most important modes of transportation for the next forty years. Now, the California St. line is only one of three remaining cable car lines in San Francisco. This particular line was put in by none other than Leland Stanford (sound familiar?). Stanford, whose mansion was just up the street on Nob Hill, made a vast fortune putting in railway lines around the country. He remains one of the Bay Area’s most controversial figures, as the Chinese laborers who laid the rails for his business were vastly underpaid and extremely overworked.

If you are interested in learning more about the history of the San Francisco cable car, visit the Cable Car Museum on the corner of Mason St. and Washington St. You can also access all riding information on the San Francisco Cable Car website here: http://www.sfcablecar.com/riders.html.

Stop F. Old St. Mary’s Cathedral (1853)

One of the longest standing structures in San Francisco, Old St. Mary’s Cathedral was once the tallest building in the city. St. Mary’s was originally built to be the seat of the Catholic Church in San Francisco. Commissioned by San Francisco Bishop Joseph Alemany of Spain and designed by architects William Craine and Thomas England, the cathedral was designed to replicate a gothic church in Alemany’s hometown of Vich, Spain. The cathedral was dedicated at Christmas Midnight Mass in 1854 and continually grew from that point on. By 1881, however, it was decided that the cathedral would no longer remain in the declining neighborhood. The structure remained and was eventually put under the charge of a Paulist order of priests (and the new St. Mary’s Cathedral was later built on Geary St.). The Paulists had long run a Chinese Mission and brought this to St. Mary’s, thus making it an integral part of Chinatown. This same order of priests continues to run the church today. The church went on to withstand both the 1906 and 1989 earthquakes, and three of the walls are original. You are welcome to go quietly inside the church, even while Mass is going on, as there is a designated historical section in the back of the church. Before you go inside, take a look below the central clock. The words read, “Son, Observe the Time and Fly from Evil. Ecc. 4:23.” Some believe those words were put there to turn men away from the brothels located directly across the street.

Walk up to the corner of California St. and Grant Ave. Look across Grant at the two corner buildings, known as the Sing Chong and Sing Fat Buildings.

Stop G. Sing Chong Building (1907)

The oldest piece of Chinese architecture in San Francisco, this building was actually designed by a Scottish architect. Thomas Patterson Ross, an Edinburgh native, was a major architect in San Francisco following the 1906 earthquake and most well known for the Alcazar Theater he designed on Geary St. His design for Sing Chong, as well as the neighboring Sing Fat building across the street, represented a shift in post-earthquake San Francisco. Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans pushed to create a “city within a city.” Sing Chong proprietor (and First Bank of Canton founder) Look Tin Eli recommended the pagoda style architecture to entice tourists into Chinatown.

From the corner of Grant and California, continue heading down Grant. The next street you reach will be Sacramento St. Make a right turn on Sacramento and stop when you reach the Nam Kue School building.

Stop H. Nam Kue School (1919)

A small Chinese-style building gated and drawn back from the street, Nam Kue School first opened its doors in March 1920, though the idea for it came about a year prior. At the time, a group of prominent Chinese-Americans in San Francisco decided something must be done to preserve Chinese culture with future generations, so this and several other schools opened for American-born Chinese children. Taught history, culture, and language, the Nam Kue School continues to welcome children through its doors. Up until 2005, the school flew the flag of the Kuomintang, also known as the Chinese National Party. The Kuomintang, started by Sun Yat-sen, opposed both the Qing dynasty and the emerging presence of communism in China. In 2005, because of better relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, the Kuomintang was replaced with a People’s Republic flag.

Just next to Nam Kue School is Kee Photo. Take a look at all the photos on their front window. The owner, Mr. Kee, has photographs of himself with celebrities and entrepreneurs on display. Look closely and you’ll see former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, Microsoft’s Bill Gates, and many more. If you happen to need passport photos, apparently Mr. Kee is quite cheap and efficient with those.

Head back up to Grant Avenue and make a right turn onto it. Continue walking along Grant until you reach Commercial St. On the Commercial St. side of the Eastern Bakery, there is a wall of murals. In 2010, British street artist Banksy left his mark with a ‘Peaceful Hearts’ Doctor image on the wall. Though there were efforts to preserve the work, it was eventually sprayed over. The murals on this wall are ever-changing, so take a look and enjoy.

After looking at the street art, head on along Grant Ave. to Clay St. Make a right turn on Clay and look at the murals on both sides of the street.

Stop I. Clay Street Murals

On the left side of the street (on the side of Asian Image) is a beautiful map/mural/calendar. Not only does it show the upcoming years and corresponding animals from the Chinese calendar, but also a map of Chinatown. On the right side of the street is a darker mural, entitled Chinatown 1889. Painted to capture the difficult history of the Chinese in San Francisco, the first thing you may note is that the figures in the mural are primarily male. Up until about the turn of the century, the majority of Chinese immigrants were young men coming to America for work. From the early 1880s through the beginning of World War II, Chinese immigrants had to face the realities of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The goal of the act was to keep the number of Chinese immigrants to the city down, though by World War II, with China as an ally, the act was repealed. In the mural, you may also see a man holding a card with a red L on it. This referred to the lottery system within Chinatown; it was not a lottery for money, but for work and housing.

Continue down Clay St. (on the side of the calendar/map mural) and make a left into Portsmouth Square.

Stop J. Portsmouth Square

Named for Captain John B. Montgomery’s ship, the USS Portsmouth, this is one of the oldest established areas in San Francisco. Captain Montgomery (whose namesake street is only a few blocks away) rode into the San Francisco Bay in 1846 to officially seize Yerba Buena (San Francisco’s former name) for the United States. He then planted an American flag in this public area and soon after, Portsmouth Square became one of the most important in the growing city. This is where the discovery of gold was first announced in 1848. The first city hall and public school sprang up in this square, and it thrived as the center of the city for much of the post-Gold Rush period. Eventually, as the city shifted its focus toward the Market St. area, City Hall was replaced closer to its present location. With the shift toward Market St., Chinatown began expanding into Portsmouth Square. Now, the sight of the first American flag is considered the very heart of Chinatown. Most frequented by a more elderly crowd, you’ll see separate groups of men and women sitting on cardboard boxes and crates playing cards or the traditional game of mahjong. Bustling with activity, take some time to wander around the square and enjoy.

There remains a plaque commemorating John B. Montgomery’s placement of the American flag, as well as another commemorating the first public school. There is also a monument dedicated to author Robert Louis Stevenson, who is said to have frequented Portsmouth Square while he was in San Francisco.

As you walk into the square, you will see a statue. This is the Goddess of Democracy.

Stop K. Goddess of Democracy Statue (1994)

For a more in-depth look at the Goddess of Democracy, check out this article from the New York Times Sinosphere blog.

While standing in Portsmouth Square, look eastward across Kearny St. You will see a footbridge connected to one of the most unsightly buildings in San Francisco. This building, part Hilton Hotel, part Chinese Culture Center, is where much planning and preparation occurs.

Stop L. Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco

You are welcome to enter the Chinese Culture Center to appreciate many different art projects, cultural workshops, and educational information. The Chinese Culture Center, in existence since 1965, works to bring intercultural understanding to the city and its visitors. For full information on visiting and present exhibits, visit the CCC website here.

Located at the corner of Kearny and Washington (northeastern corner of Portsmouth Square) is Buddhas Universal Church.

Stop M. Buddhas Universal Church

The largest Buddhist church in the United States, this building (a former nightclub and gambling house) has kept its doors open to followers and visitors since the early 1960s when it opened. Though the exterior is not exactly impressive, take a tour inside to appreciate the beauty and tranquility of this church. For a complete history, we feel it best to read the church’s own website here.

After leaving Buddhas Universal Church, start walking up Washington St. Just past Portsmouth Square on the left (and before Grant Ave.), you will see the Bank of Canton.

Stop N. Bank of Canton

This ornate building was once the home of the Chinese Telephone Exchange. The Exchange, which began small switchboard operations back in 1891, expanded and grew in this location until the 1906 earthquake destroyed it. Following the destruction of the earthquake, the Exchange was rebuilt in a decorative Chinese-style building. It remained there until 1949 when switchboard operations were no longer necessary. The building was eventually bought by the Bank of Canton in 1960 and has remained its since.

Continue up Washington St. until you reach Waverly Place. Make a left onto Waverly and walk about halfway down the block. On your right, you will see Sun Lam Florist. Next to this shop is a set of stairs leading up to the Tin How Temple. Look closely, or you may miss the sign.

Stop O. Tin How Temple

The oldest established Chinese temple community in the United States, the current location of the Tin How Temple postdates the 1906 earthquake. The original Tin How Temple was opened in 1852 in honor of the goddess Mazu. The first Chinese immigrants gave thanks to Mazu, Goddess of the Sea, for their safe passage across the Pacific to their new home. To reach the temple, you’ll have to climb about three flights of stairs to the top floor of the building (there is no elevator access). When you reach the top floor, you’ll enter a vibrant and aromatic vermilion room. Though you are not allowed to take photographs, you’ll leave with lasting images of the various shrines, red lanterns hanging from the ceiling, and stunning views of the Transamerica Building and Coit Tower from the balcony.

The Tin Temple is open to the public from 9am to 5pm daily. It is still an active temple. You can leave a donation at the entrance if you are so inclined, and you can also get your fortune read inside.

After leaving the Tin How Temple, retrace your steps down Waverly back to Washington St. Cross Washington and walk downhill until you reach Ross Alley on the left. It is not far from Waverly, so if you reach Grant, you’ve gone too far. When you turn onto Ross Alley, walk toward the opposite end and stop when you reach the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory on the right.

Stop P. Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory (1962)

For more information on the history of the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory and the invention of the fortune cookie, visit our blog post here.

Make a right turn out of the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory, but stop just a few feet away in front of the green front of Jun Hu’s Barber Shop.

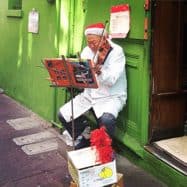

Stop Q. Jun Hu’s Barber Shop

One of Chinatown’s most beloved celebrities runs this little hole-in-the-wall barber shop. Located just next to the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory, the 80-something year old Jun Hu appeared in the opening credits of the Will Smith’s 2006 film “Pursuit of Happyness.” Some say Frank Sinatra got his hair cut here, others say a Frank Sinatra im

After leaving Jun Hu’s, continue walking down Ross Alley to Jackson St. Make a right turn down Jackson, then a left on Grant. Partway down the street (on the left) is the Golden Gate Bakery.

Stop R. Golden Gate Bakery

By and large one of the most popular bakeries in Chinatown, when it’s open, the Golden Gate Bakery typically has a line out the door and down the street. While there are some tourists who make up that cue, most of those waiting are eager locals. The bakery, famed for its egg custard tarts, keeps its own hours. That means it may be closed when you show up, or it may be open. Because people are so eager to know when it is open, there is a Facebook page (Is the Golden Gate Bakery Open Today?) dedicated to tracking its daily hours of operation.

Continue walking down Grant Ave. to the intersection of Grant/Broadway/Columbus. Ahead of you is the beginning of North Beach. Across the street you’ll see a mural that wraps around the entire building. The part you are facing depicts scenes from Chinatown, while the opposite side shows the Jazz Era in North Beach. From here, you can head into North Beach or, if you would like to explore more of Chinatown, we recommend making a left on Broadway. Walk up to Stockton St. and make a left. On Stockton, you will see the Chinatown beyond the tour books. For the next few blocks, you will walk past fish markets, spice shops, vegetable stands, and more. The street will be crowded, especially on weekends, as people shop and bargain.

Thank you for joining us on this tour of San Francisco’s Chinatown - we hope you enjoyed it!