The first shots of the Civil War rang out right here in Charleston. Learn what conflicts prompted the war, what side fired the first shots, and what the aftermath and consequences were of what they called the “War between the States,” all while strolling the streets and the battery of Charleston.

If you’re taking our self-guided tour, let us know and tag us on social media @freetoursbyfoot

Civil War History of Charleston Audio Tour

You can also take this as a self-guided audio tour! We have recorded some of our best tour guides giving their tours and put them on a GPS enabled app.

We have partnered with Atlantis Audio Tours to provide you with a convenient way to experience our tours. Each tour offers an off-line option to view the map and hear the audio of each walk so that you don't need to have GPS maps running with the app.

Here is how it works:

- Purchase an Audio Tour

- Receive a confirmation email with details.

- Enjoy the tour(s).

Listen to a sample of our Civil War History of Charleston Tour.

Introduction

After the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and with the threat of abolition of slavery, representatives from around South Carolina met in Charleston to discuss the future.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina was the first state to formally secede from the Union. In addition to the formal Ordinance of Secession, they issued a Declaration of Immediate Causes, which stated:

"We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the right of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection."

The South Carolina militia and later Confederate Army remained in control of Charleston and the harbor for much of the Civil War until February 1865.

We start our tour at the Market Building at 180 Meeting Street. The tour will end about two blocks away from here. If you're interested in other things to do in Charleston before or after the tour, check out our blog post about the top things to do in Charleston.

We also offer guided tours of Historic Charleston and the architecture of Charleston throughout the week. Find out more on our website linked here.

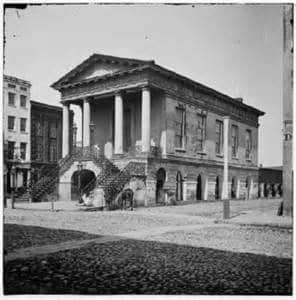

Market Building/ Daughters of the Confederacy Museum - 180 Meeting St

This 1841 building was built in the style of an Athenian temple to serve as the "front office" of the local farmer's market. In addition to small office space, it was used as a public hall where social functions and meetings were held prior to the American Civil War. After the declaration of war in 1861, young men from around the area came back to this building to sign up to defend the South. It was here they were given their weapons and orders.

In 1899, the city used donations from Confederate veterans - among them being the Mayor and city councilmen of Charleston - to establish the Confederate Museum. Today it is run by the Daughters of the Confederacy. As many of the items were donations from locals who served in the Confederate Army, you'll find uniforms, weaponry and personal items. If you are interested in visiting the museum, admission is included for free on the Charleston Tour Pass, which we review and explain on this link. Other sites on this tour including the Old Slave Mart, and the Old Exchange Building are also included on the pass.

Head south on Meeting St (with the Market Hall behind you, turn left) to the first stop. You'll see a small plaque on the side of 126 Meeting Street in two blocks, labeled Ordinance of Secession.

Former location of S.C. Institute Hall (Secession Hall) - 126 Meeting Street

This is the site of the South Carolina Institute Hall. Built in 1854, this was the largest public exhibition hall in 3 states and could hold 2500 people.

It was the site of the contentious first Democratic Convention in April 1860. Slavery was a dividing issue in the party and the Southern delegates endorsed a pro-slavery platform. When the Democratic platform was adopted it did not include endorsing the Dred Scott decision or protecting slavery in new territories. This divided the delegates and most of the Southern representatives left in protest. The convention would fail to agree on a nominee and would reconvene in Baltimore later, nominating Stephen Douglass, who did not have the support of the Southern delegates, as the Democratic candidate. In fact, many of the Southern delegates who let the convention in Charleston would nominate their own candidate, John Breckenridge. The division would result in the election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. Though we refer to the political parties, Republican and Democrat, which are also the same names of modern parties, the parties are very different today than in the 1860s and should not be considered the same parties - even though they use the same names.

With the election of Abraham Lincoln, who had little support in the South, and what that meant for slavery, South Carolina would vote to secede from the Union.

On December 20, 1860, recently elected state officials gathered with family and friends to witness the signing of the "Ordinance of Secession" pulling South Carolina out of Federal statehood. They voted 169 to 0 to secede.

South Carolina was the first state to secede, shortly followed by other Southern states that would then form the Confederate States of America. South Carolina delegates later ratified the Confederate Constitution here on April 3, 1861.

On December 11, 1861, what became known as Secession Hall was lost to the ‘Great Fire of 1861

Continue south on Meeting Street to Queen Street. You'll want to cross over to the far corner to reach the right side of the street and the next stop.

Mills House Hotel

115 Meeting St

Originally built by a local grain merchant, Otis Mills in 1853, the "Mills House" was a 180 room hotel during the Civil War.

The building was rebuilt in 1968, but the cornices and ironwork are the original from this mid-19th-century hotel.

The building survived destruction during both the 1861 fire and the Civil War. In fact, Confederate General Robert E. Lee was having dinner at the hotel when the Great Fire of 1861 began on December 11, 1861. He had just returned from inspecting the city's defenses.

Continue south to the next building on your right.

Hibernian Hall

105 Meeting St

The Hibernian Society was founded by Charleston's elite Irish immigrant merchant class to aid other Irish families in establishing themselves in Charleston. This hall was built in 1840 in the Greek Revivalist style.

When the April 1860 Democratic Convention split over nominee and slavery, some of the delegates moved here - meeting on the first level and sleeping in cots on the second.

Once the Ordinance of Secession was signed, Hibernian Hall was used by the "Republic of South Carolina" as its first and only government capital building (Dec. 1860- April 1861) which is when the Confederate States were unified.

Continue south on Meeting Street. The next intersection is known as the Four Corners of Law. Each corner has a different city, state, federal, and religious building. Charleston City Hall and Charleston County Courthouse were both standing during the Civil War, but the Post Office was built in the 1890s and during the Civil War, an armory and guardhouse stood at this location. But we want to focus our next stop on the church on the southeast corner.

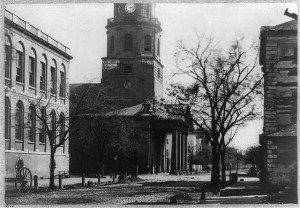

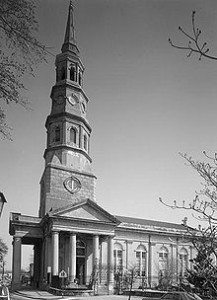

St. Micheal's Church

80 Meeting St.

St. Michael's is the oldest standing church in Charleston, built in 1761, and has always been the house of worship for the city's finest families, including the wealthiest plantation owners. Because of this history, this church was the main target used by Union-controlled sea island fort guns surrounding the city.

St. Michael's tall steeple had been used as a lookout during the Revolutionary War and again during the Civil War. But just as the watchmen could see beyond the city from this tall vantage point, the steeple could be seen from Union cannons on nearby Morris Island. To protect the church, the bell tower was painted gray to blend in with the horizon so it would not stand out in the city skyline.

From August 1863 through February 1865, Charleston was shelled on a daily basis, ending when the city was evacuated by the Confederates. In fact, if you're able to go inside, there is a scar at the foot of the pulpit from a shell that landed during the Civil War. Also look for the large, long double-pew in the center of the church, No. 43. This is where Robert E. Lee would worship during his time in Charleston (its also where George Washington sat during his visit to Charleston)

Continue south down Meeting Street. You'll want to cross back over to the right side of the street after crossing Tradd Street for our next stop at 37 Meeting Street.

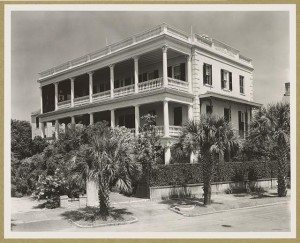

Simmons/ Mills House

37 Meeting St.

This house was built in 1760 as a private residence for a local lawyer James Simmons. Nearly a century later, it was the home of Otis Mills, owner of the Mills House hotel, and was in use by General Beauregard as his headquarters until August 1863 when Federal shelling forced him to move further north in the city to what is now the historic Aiken-Rhett House, the same location that Confederate President Jefferson Davis stayed in during his visit to Charleston.

It was during this second command of Charleston, the Beauregard successfully repelled multiple Union naval attempts to take control of Charleston.

Continue south on Meeting Street to the large Calhoun Mansion, standing on the left just after Atlantic Street.

Calhoun Mansion (George Williams House)

16 Meeting St.

Built nearly 10 years after the Civil War ended, this is the largest private home in the city, nearly 25,000 sq ft.

It was built by George Walton Williams, who was one of the richest men in the city after the Civil War for a very interesting reason. During the Union blockade of Charleston Harbor, where it was difficult to get supplies through the Union naval lines into the city, Williams funded the successful blockade runners who could skirt past Union forces. He only accepted payment in gold and silver. When the Confederacy collapsed, he still had the worthwhile gold and silver, instead of the Confederate currency that had been used in Charleston for years prior.

He built this house at the cost of $200,000, which is more than 4 million today.

George Williams was a member of the City Council and was chosen to offer the surrender of the city from Charleston Mayor Charles McBeth to Union Lt. Col. Augustus B. Bennett of Sherman's Army on Feb.18, 1865. This effectively ended the war for the people of Charleston.

Go south on Meeting Street until it dead-end and cross the street to White Point Gardens

White Point Gardens

While we go over the history and memorials in White Point Garden, you can either listen to this stop here and then explore or walk and listen. You'll want to head to the far corner, at the tip, where East Battery and Murray Blvd meet.

This southern tip of Charleston was always a public park. During the Civil War, you would have found a bathhouse with an ice cream parlor on the far end of the park to the right. The size and shape of the park have changed through the years as landfills and fortifications have reshaped the point.

In 1861, White Point was converted into a large fortification of earthworks spiked with large cannons to protect the lower part of the city from attack by the Union armies.

Today, there are many military relics in the park.

When you first enter the park, you'll see a memorial to the crew of the HL Hunley. The Hunley was a Confederate submarine (though it was not complete submerged) and was the first to successfully sink a warship. The Hunley also sank during this attack - it is thought she was too close to the USS Housatonic when the torpedo exploded - and lost the crew of 8 men.

You'll find various cannons spaced along the perimeter. To your left, along the waterfront on East Battery is an 11-inch Dahlgren gun from the USS Keokuk. This Union ship fired shells at Fort Sumter in 1863 but was eventually sunk. Confederate forces salvaged what they could from the ship. There are also two Confederate cannons that were used in the defense of Fort Sumter. In front of you on the waterfront on Murray Blvd. you'll find a large cannon fro Fort Johnson and four 13-inch Union mortars (weighing 17,000 pounds each).

Where East Battery and Murray Blvd meet at the tip, you'll find the memorial to the Confederate Defenders of Charleston. It was erected in 1932 and features an allegorical statue of a man with a shield, featuring the South Carolina state seal, standing in front of an Athena-like woman. While the dedication ceremony was attended by the last surviving Confederate veteran from Fort Sumter, this statue was dedicated nearly 70 years after the Civil War during the Jim Crow era and racial segregation. As with many Confederate statues, there is controversy over whether this memorial should remain as is or at all. There are no current plans to remove any statues but Charleston civic leadership has suggested the need to add context to them.

Cross the street from the Confederate Defenders statue to walk up the stairs to the Battery Wall. Listen to the next stop as you walk along the battery walk, keeping the water to your right. You'll want to be sure to stop at the seventh house on your left, but you can also just look for the black signpost on the sidewalk for the Edmonston Alston House.

Battery Wall

This wall (c. 1820) is where the citizens of Charleston watched the bombardment of Fort Sumter by the newly founded South Carolina militia.

When South Carolina seceded from the Union in December of 1860, the Union troops stationed at Fort Moultrie in the harbor moved to Fort Sumter, as it would be more easily defendable. Confederation General Beauregard and South Carolina government repeatedly called for the surrender and evacuation from both the federal government in Washington DC and the Union command at the fort, Major Robert Anderson.

With Anderson's refusal to surrender the fort, the Confederate forces would prevent any resupply of troops or goods to the fort. The Union troops at Fort Sumter would run out of food in April. Resupply attempts were made but deterred by cadets at the Citadel in Charleston.

The first shot was fired at 4:30 am on April 12, 1861, from Fort Johnson on Johns Island (the second island on the right from where you are standing). The firing continued for 34 hours & there were no casualties reported from either side.

It wasn’t until the evacuation of Fort Sumter after the surrender that an overheated cannon exploded 2 soldiers died of their injuries.

Thus, it is said that the first battle of the Civil War was “ bloodless” as the incident happened after the battle ended.

All the while, Charleston residents stood atop this wall and nearby balconies watching the bombardment and drinking salutes.

If you're interested in visiting Fort Sumter, the only way to do this is on the official Fort Sumter Cruises. You can find details on this option at this link.

By now you should have reached 21 East Battery St.

Edmondston/ Alston House Museum

21 East Battery St

During the bombardment of Fort Sumter, owner Charles Alston sent General P.G.T. Beauregard an invitation to dine and rest in this circa 1825 house.

The last 4 hours of the battle were commanded by Beauregard from the second-floor gallery of this home.

Later that year when the Great Fire of 1861 crept too close to the Mills House Hotel where Robert E. Lee was staying, Lee was invited to stay at this house.

The Edmondston-Alston House is still owned by the Alston descendants & is open to the public as a house museum featuring family treasures of furniture and silver & original documents related to the family’s role in the War starting in Charleston, including an original copy of the Ordinance of Secession & a copy of the federal pardon signed by President Andrew Johnson so the family could have their confiscated properties returned.

Continue along the battery wall until you reach the end. Look for the brick building on your right and the historic marker on the sidewalk.

Headquarters of Historic Charleston Foundation

40 East Bay St.

The Historic Charleston Foundation is headquartered at this site.

In 1862, it was just east of here in the Charleston Harbor that an enslaved man, Robert Smalls, commandeered the CSS Planter and piloted through the Federal blockade to freedom.

Smalls had been part of the crew of the Planter for a few months when on the night of May 12, 1862, he put into place his plan to escape. As the white officers spent the night on shore, it was custom for Smalls and the other enslaved men to spend the night on the boat. At 430am, he put on a captain's uniform and straw hat that the Confederate Captain Relyea usually wore. He piloted the ship to another dock to pick up the family members and then was easily able to sneak past the Confederate ships by mimicking the captain's mannerisms.

As the small ship came upon the US Navy, they raised a white bedsheet and found freedom with the federal forces and delivered to them the cargo that was aboard the Planter - four large guns, ammunition, firewood and the Captain's logbook with Confederate codes, and maps showing the location of mines.

Smalls would then join the Union Navy as a ship pilot, including on the Planter. After the war, Smalls would return to his hometown of Beaufort and purchase his former master's home. He would be elected to Congress as a representative for South Carolina, serving different districts from 1875 to 1887.

Continue along East Bay to 51 East Bay St.

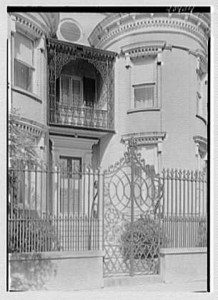

John Fraser Mansion

51 East Bay St.

This house was built circa 1799 by a German merchant. It was bought in 1821 by John Fraser, a wealthy shipowner and cotton broker.

Fraser and his partner, George Trenholm, had a fleet of 60 commercial ships. They would slip past the Union warships blocking the mouth of Charleston Harbor, delivering goods for sale to Liverpool, England and returning with ammunition and luxury goods. The overseas branch of the firm became the official banker of the Confederate Government and it is said the company made nearly $9 million running the blockade.

Continue North on East Bay Street to the Old Exchange Building, which will be on your right.

Old Exchange Building

122 East Bay St.

This 1771 colonial-era town hall/exchange was later used as the city's post office from 1820-1865.

Prior to the Civil War, the area around the Exchange building, and sometimes inside, was used prominently for the sale of enslaved persons. Charleston was one of the busiest slave-trading ports, starting in the 1770s. By the mid-1800s, just before the Civil War, this part of Charleston was the busiest and most well-known areas for slave auctions. Many of the enslaved persons sold here were domestic and born in the US. After the public auctioning of enslaved persons was banned in 1856, the trade was moved indoors.

During the Civil War, the building continued its normal function as the city's post office and customs house by the Confederacy until it was abandoned after being shelled by Union artillery. After the surrender of Charleston, occupying Union officials used this building as a commissary for the recently emancipated slaves flooding into Charleston after the war.

You can stop and visit inside the Old Exchange Building to learn more about its history, including a tour of the dungeon which focuses on its Revolutionary War history.

The road directly in front of the Old Exchange is Broad Street. Head up Broad Street and turn right onto State Street at the first intersection and then left onto Chalmers Street. The next location is on your right.

Old "Slave Mart" Museum

6 Chalmers St

Built in the 1850s, this was one of an estimated 40 slave auction houses in a 3 block radius serving Charleston's demand for new slaves at the plantations. This building was originally part of a larger complex, known as Ryan's Mart, that would have included a building known as a barracoon, which held enslaved men and women waiting to be auctioned, a jail, a kitchen, and a morgue.

The last enslaved person sold here was in 1863. When the Union forces took command of the city, the remaining enslaved persons inside the Slave Mart were freed.

The Slave Mart Museum is open to visitors with admission cost unless you have a tourist discount pass. It interprets the history of Charleston in the international and domestic slave trade.

Continue west on Chalmers Street to Church Street and turn right. Continue halfway down the block. The next stop will be on your left.

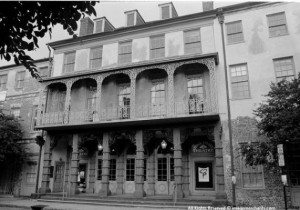

Dock Street Theatre (Planters Inn Hotel)

135 Church St

Now the site of a theatre, this 1850s building was the original Planter's Inn hotel. The wealthy plantation owners used this hotel during the Charleston social season (Christmas through Spring planting) until the war.

Junius Brutus Booth performed here - he was the father to actor John Wilkes Booth who would assassinate President Abraham Lincoln towards the end of the Civil War. And before his escape on the Planter, Robert Smalls was a waiter here.

Union soldiers were quartered in the hotel during the occupation in 1865.

Head across the street for our next stop.

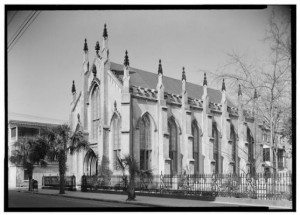

French Protestant (Huguenot) Church

136 Church St

This is the 3rd church on this site, the French "Huguenot" church was established in 1685 but the structure you see was built in 1845. During the early occupation in February 1865, members of an Ohio regiment looted the church and stole most of the hymnals and bibles. The organ was dismantled and loaded aboard a ship bound for the North. Legend says the ladies of the congregation marched down to the dock and demanded it's return. The original organ is still played on Sunday.

Walk towards the next church down the block.

St. Phillips Church

146 Church St

Still serving the city's oldest families, St Phillips is the oldest congregation in Charleston, founded in 1682. This current church was built in 1838. The original bells were donated by the church and melted down to make cannons for the Confederacy.

Though General Beauregard had successfully repelled Union navy attacks in Charleston Harbor, as Union General Sherman marched through South Carolina, it became evident that the city was at risk from inland. Beauregard ordered the evacuation of Confederate troops on February 15, 1865, and three days later Union troops occupied the city. The first Union soldiers to enter the city were members of the 21st Infantry Regiment of the US Colored Troops and the 55th Massachusetts Infantry - both black regiments.

You can follow Church Street to the Market area to end your tour in the city's market.