This self-guided tour takes you through a section of the city with a large density of 18th-century sites, including those open to the public for free and some that that charge admission.

- Self-Guided Tour

- Audio Tour Option

- A Brief History of Charleston

- Nearby Attractions

- Walking Tours of Charleston

As an alternative to using the below self-guided tour, you can now use one of our affordable AUDIO TOURS!

We have partnered with Atlantis Audio Tours to provide you with a convenient way to experience our tours.

Of course, you can always join our pay-what-you-wish walking tours of Charleston.

But our audio tours of Charleston give you the chance to be led by an experienced tour guide at a time of your choosing.

The tour is also available with an off-line option to view the map and hear the audio of each stop so that you don't need to have GPS maps running with the app.

Here a sample of the tour. "The Dock Street Theater".

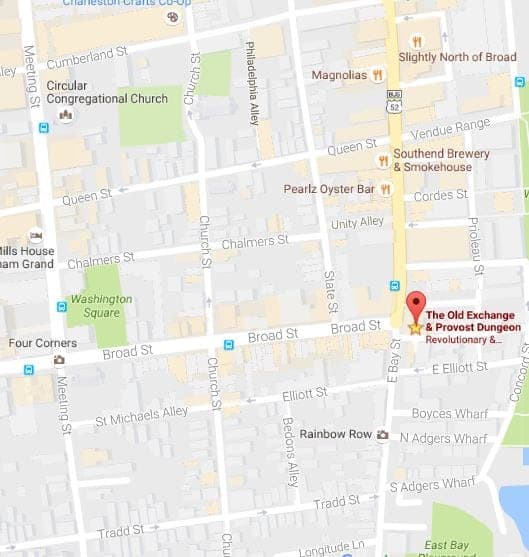

This self-guided tour starts at the red marker on the map at the intersection of East Bay Street and Broad Street.

With houses and buildings that have remained intact since before the American Revolution, Charleston allows your imagination to travel back in time to the when stately horse-drawn carriages rode down quaint cobblestone streets.

It also is a reminder of America's darker past when slavery was legal and Charleston was one of the biggest hubs of the slave trade.

This tour was designed to show you both sides of the city.

(1) The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon, East Bay Street at Broad Street

By the 1770s Charleston’s population was around 12,000 people, half of whom were slaves. In one year, over 7,000 black Africans were channeled through the city to other parts of the colonies.

The city’s commercial center was Bay Street, anchored by the Custom’s House (Exchange Building) where public slave auctions were held outside and along the adjacent factors’ wharves.

Other enterprises included brokers’ offices and a large number of merchants who catered to the maritime trade. Rope, tar, lumber, canvas, and nails were kept in good supply.

Great sailing ships arrived with bulk cargo from Europe, while smaller boats and canoes arrived via the local waterways loaded with animal skins, corn, and other goods.

Walk west on Broad Street, turn right on State Street, walk one block north and then left on Chalmers Street, one of the few remaining cobblestone streets in Charleston.

(2) The Old Slave Mart 6 Chalmers Street

The building at this site, which now houses the Old Slave Mart Museum, is the only surviving building in South Carolina that had been used as a slave auction gallery.

In the antebellum period, the era leading up to the Civil War, Charleston was a commercial center for the plantation economy. Where there were plantations, there were slaves.

The Old Slave Mart was built in 1859 as a result of a city regulation that prohibited public sales of slaves.

The Old Slave Mart made it possible for the slave trade to continue in Charleston now that it had been moved to an indoor private location. It only operated for four years, closing its doors in 1863 in the idle years of the Civil War.

Two years later, slavery would be abolished in all the United States. After 1865, the building’s ownership and use changed many times. Between 1878 and 1937 the building was a tenement for African-Americans.

In 1938, Miriam B. Wilson purchased the building, called locally the Old Slave Mart. Wilson established a museum featuring African and African-American arts and crafts.

In 1964, Judith Wragg Chase and Louise Wragg Graves took over the Old Slave Mart Museum and got the Old Slave Mart building placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and operated it until 1987.

The City of Charleston bought the property in 1988, having recognized its importance in the history of the slave trade in Charleston.

(3) The Old Slave Mart Museum located inside the Old Slave Mart

The museum displays accounts, many firsthand, of the slave trade from freed slaves told through photos and writings on display. There are very few objects or interactive exhibits so children may be bored.

If you don’t know much about the history of the slave trade, you will find the museum interesting. It will take under an hour to go through the museum.

Hours and Admission: Open Monday-Saturday. $7 (adults 17 and up); $5 (ages 5-17 and seniors 60 and older); children under 5 free.

Continue on Chalmers Street one block.

(4) The Pink House 17 Chalmers Street

Built around 1712, the Pink House is believed to be the second oldest remaining structure in Charleston. It never was a house; rather it was a tavern and rumored to have housed a brothel on the upper floor.

The Pink House was just one of the structures along cobble-stoned “Chalmers Alley” part of the bawdy, rollicking tavern and bordello district that lay adjacent to the wharves. It remained a tavern through the 1700s when the neighborhood became more residential.

Since then it has been a publishing house, a law office and is now an art gallery. Some say that the Pink House has, from time to time, “visitors” long since departed from this earthly world.

Turn right on Church Street and walk about half a block.

(5) The Douxsaint-Macauley House 132 Church Street

In 1726, a house was erected by a French Huguenot Paul Douxsaint. This is noted on the historic marker next to the front door.

The first house burned down in the massively destructive fire of June 13-14, 1796. (Because of the close proximity of the houses in this area, the fire spread rapidly. It has been estimated that at least 300 families had lost their homes in the blaze).

The current house here was built after the fire and remains a fine example of early Federal period homes with its beaded weatherboarding on the exterior, 9-over-9 windows, and a roof with dormers.

In the 19th century Daniel Macaulay, a member of one of Charleston’s leading Scottish merchant families, owned and occupied the dwelling.

Walk about 200 feet further along Church Street until you are standing in front of a very small graveyard.

(6) The French Huguenot (Protestant) Church 140 Church Street

The graveyard belongs to the pink neo-gothic building, the French Huguenot Church. Three church buildings have stood on this site, the current one was built in 1845.

The first church building was completed in 1687, but during the great fire of 1796 was deliberately blown up to create a “firebreak” (a strip of cleared land made to prevent the spread of a fire).

The second church was built in 1800 but closed in 1823 as the congregation membership dwindled. Huguenot descendants revitalized the congregation in 1844 and the second church was razed and the current church was built.

The church came to be known as the Church of the Tides because Sunday services were held based on the tidal schedule as most in attendance came to town on boats from their up-river homes.

Throughout the 1900s, the church was used periodically by the Huguenot Society of South Carolina for special events. Today's congregation was reestablished in 1983 and is the only French Calvinist congregation in the United States today.

Across the street from the Church and graveyard, you will see an eye-catching two-story building with a balcony.

(7) The Dock Street Theatre 135 Church Street

This ornate building with its intricate wrought-iron balcony is now home to the Charleston Stage Company, South Carolina's largest professional theater production company. However, it was built as a hotel around 1809.

Named The Planter’s Hotel, it is Charleston's last surviving hotel from the antebellum period. At that time the hotel’s guests were mainly planters from around the state who came to Charleston for the horse-racing season.

The hotel was well-known for its good food and delicious alcoholic drinks. Some believe that the South's famous Planter's Punch may have been created here.

The building itself has had several additions to it over the years, as is evident from the different differences in brick coloration. The prior building from 1730 is believed to have been the first building constructed specifically for theatrical performances in America.

In 1736, the grand opening of the theatre featured a production of The Recruiting Officer by Irish playwright George Farquhar. Having left acting after accidentally stabbing a fellow actor on stage, Farquhar later served in the army as a recruiter and drew from those experiences in writing his play.

During the building’s days as the Planter’s Hotel, actors performing in nearby theaters routinely stayed at the hotel. Among the guests was Junius Brutus Booth, the father of John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin.

Cross Queen Street and walk straight ahead one block.

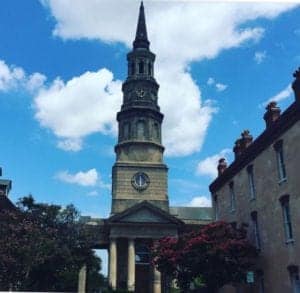

(8) St. Phillips Episcopal Church 146 Church Street

The congregation who built the current church grew out of colonial congregation who built a small wooden church in 1681. That wooden church was the first Anglican church south of Virginia.

As such, St. Phillips is home to the oldest congregation in South Carolina. In the early 18th century, a brick church was built on this site but which burned down in 1835.

The church you know see was constructed from 1835 to 1838 by architect Joseph Hyde. Many notable people from the colonial era and post-Revolutionary War years are buried in the graveyard. Several colonial governors are interned there, including Rawlins Lowndes, the governor during the Revolutionary War.

Prominent early Americans are also buried there such as Christopher Gadsden, a general in the Continental Army, Daniel Huger, a member of the Continental Congress, Edward Rutledge, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and Charles Pinckney, a signer of the U.S. Constitution.

Note: The building and graveyard are open to the public Monday-Friday, 10:00 am to 12:00 pm and 2:00 pm to 4:00 pm.

Turn left on Cumberland Street.

(9) The Old Powder Magazine 79 Cumberland Street

This building is so old that when it was built the word magazine had only one meaning – it was an arsenal of gunpowder from 1713 until 1748.

At that time, the colony was young and was afraid of attacks by Native Americans, and French or Spanish forces also staking a claim in the New World.

The city was so fortified that the colonists built a wall around it, making Charleston one of only three fortified cities on the entire eastern seaboard of British Colonial America. The magazine is also the oldest public building in the state of South Carolina.

By the 1740s the colony was fully protected by the British Crown and the local government felt the magazine was no longer necessary.

Although it was used as an arsenal again during the Revolutionary War, after that the building served as a stable, a print shop and a carriage house.

In 1902, the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in The State of South Carolina bought the building to ensure its preservation as a historical landmark. They converted the magazine into a museum and it has remained one ever since.

The museum is just one small room, as you can see from the size of the building. For history buffs and guns, powder and cannon enthusiasts, a visit might be worth your while.

Many people enjoy the thrill of being inside a building over 300 years old. The staff is enthusiastic and very knowledgeable and there is a diorama of the city when it was walled. Who doesn’t love dioramas!

Hours: Monday to Saturday 10:00 am - 4:00 pm and Sunday 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm. Admission is $5 for adults and $2 for children.

Walk half a block north on Cumberland to Meeting Street. Turn left on Meeting Street and about halfway down the block you will see the church and a gated path that enters the graveyard of the church.

(10) The Circular Congregational Church 150 Meeting Street

In 1681, Charles Town settlers including English Congregationalists, Scottish Presbyterians, and French Huguenots built a wooden meeting house in the northwest corner of the walled city.

As non-followers of the Anglican Church, these settlers were considered dissenters and as such was not allowed by law to call their place of worship a ‘church'.

They were allowed to call it a meeting house, and the street that led to the wooden building was called "Meeting House Street” later shortened to Meeting Street.

The current church building stands on the exact site of the wooden house. A century after its construction, the wooden meeting house was replaced with a circular brick building designed by esteemed architect Robert Mills.

That church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1861. In 1890 the present-day church was constructed. The church is striking due to its Romanesque style that stands out among the surrounding buildings.

The graveyard is the city’s oldest burial ground with monuments dating from 1695. Among the gravestones, 50 slate stone markers were imported from New England and constitute the largest cluster of that region’s carvers in the Southeast.

If you are not easily spooked, take our Charleston Ghost Tour and learn more about the "residents" of the Circular Church's graveyard.

Follow the path in the graveyard and you will exit onto Meeting Street.

(11) Meeting Street

In 1861, a devastating fire ripped through the city and Meeting Street (between Cumberland Street and Church Street) was one of many streets whose buildings were burned to the ground, including the second Circular Church.

The fire started from an unknown source on the night of December 11, 1861, and burned a trail through the city until 5 am on December 12. The blaze covered 540 acres and over 500 hundred buildings were burned to the ground.

More than a third of the city was gone. At the time, the damages were estimated to be $7 million dollars. This fire caused more damage to Charleston than did the damage caused by the events of the Civil War.

The image on the right shows the scope of devastation along Meeting Street (image from Library of Congress).

At 108 Meeting Street, you will find a Visitor Center housed in a former Esso gas station. This is a great place for a pit-stop for restrooms, cold drinks, and sweets. There are exhibits on local history and special events are dynamic and informative.

The gift shop features a fully-stocked book store, loaded with works on history, architecture and public figures. Better still, purchases are tax exempt!

Hours: Monday- Saturday 9am-6pm, Sunday 12pm- 5pm.

Continue south one block until Broad Street. The intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets is known today as the "Four Corners of the Law" since the four buildings situated here represent four arms of law -- city, state, federal and clerical.

(12) City Hall 80 Broad Street

This hub of municipal government was constructed between 1800 and 1804 on the site of the city’s meat market from 1739 until it was destroyed by fire in 1796.

Free tours are offered and feature portraits of key Revolutionary War figures, including an odd portrait of General George Washington. There are public restrooms and a rest area, as well as an early town archaeological exhibit on the first floor.

Note: This is a secured public building, and visitors to the upper floors must pass through metal detector screening before getting on the elevator.

Look across the street to the northwest corner of the Four Corners of Law.

(13) Charleston County Courthouse 84 Broad Street

The Charleston County Courthouse is one of the most significant buildings in South Carolina as it served at the provincial capital for the state when it was still a British colony.

The first building was in 1753 and it was here in 1776 that the first public reading in the colony of the Declaration of Independence took place on the second story balcony overlooking Meeting Street.

The first building was destroyed by a fire that occurred towards the end of the Revolutionary War and a new building was erected in 1792.

The building took another hit as it was badly damaged by Hurricane Hugo in 1989. It has since been restored to its 18th-century splendor.

Note: Before entering you must inquire at the entrance whether the building is open to the public because sometimes private events are happening. If it is open, you will have to pass through security screening by guards at the door.

Look across the street to the southwest corner of the Four Corners of Law.

(14) Post Office and Federal District Court 83 Broad Street

Built in 1896 in the Renaissance Revival style, this attractive building is the federal element on the Four Corners of the Law.

The post office is on the first level and above are the courtrooms. You can walk in during normal business hours and you should. It’s simply sumptuous.

The interior is palatial with balustrade balconies, carved mahogany woodwork, a marble staircase, brass and ironwork, and stone columns. Who knew that buying a stamp could make you feel like royalty.

Cross over to the southeast corner for our next stop.

(15) St. Michael’s Episcopal Church 71 Broad Street/80 Meeting Street

Here is the ecclesiastical corner of the Four Corners and it is the oldest and the oldest church in Charleston. The church was built between 1752 and 1761.

St. Michael’s congregation grew out of St. Philip's Episcopal Church a few blocks away. In fact, the first St. Philip's church stood at this site from approximately 1681 to 1727.

Then in 1751, the congregation split and St. Michael's was built. St. Michael's was the city’s focal point of Colonial resistance to the British. The church steeple was an easy target for British ship gunners.

At one point, the congregation had the steeple painted black hoping to decrease its visibility. The reverse effect occurred and it was even more visible against the blue sky.

Incredibly, St Michael’s has survived hurricanes, wars, fires, earthquakes and even a cyclone with little damage.

The interior of the church has a typical 18th-century English design, with native cedar box-pews. Pew Number 43 was used by George Washington in 1791 and later, in 1861, General Robert E. Lee sat in the same pew.

The church and graveyard are open to the public Monday-Friday 8:45 am to 4:45 pm and Saturday mornings.

Continue south on Meeting Street for one block until Tradd Street. Turn left and enjoy one of Charleston’s most picturesque and historic streets, with at least 10 homes with landmark status. After two blocks you will reach East Bay Street. Make a left and walk half-way up the block.

(16) Rainbow Row 79-107 East Bay Street

Just one look and you know how this stretch of houses along East Bay Street acquired its name. This series of row houses, painted in bright colors, dates back to about 1740.

As it is near what was the waterfront district of the city back in the 18th century, the houses were owned to well-off merchants who had stores on the ground floor and lived on the upper floors.

You can read in-depth information on these festive houses in our post What is Rainbow Row?

Continue north on East Bay Street and at 112-114 you will find the next and last stop on the tour.

(17) Coates' Row 114-120 East Bay Street

This small simple brick and stone cluster of businesses and dwellings was built between 1710-1841.

A historic marker by the door of No. 120 says that "recently discovered documents and maps found in Scotland and the Netherlands" indicate that a seafarer's tavern was on this site as early as 1686, which would make this the oldest intact building in Charleston.

The entire strip of buildings came into the possession of Captain Thomas Coates & his wife Catherine around 1775. It has been known as Coates’ Row ever since.

Mrs. Coates took over Harris' Tavern, (which before that was The Tavern on the Bluffs) and renamed it "Mrs. Coates's Tavern on the Bay."

Regardless of the name, the taverns on that site were a happy site for thirsty sailors pulling into port and seeking grog, rum, and flavored beer.

Be sure to ask the storekeeper at the liquor store about the secret tunnels that run from under the row.

Just north of Coates' Row is Old Exchange Building, where your journey through historic Charleston began.

In 1670 English settlers pulled into port on the west banks of the Ashley River. They named their settlement Charles Town in honor of King Charles II of England.

Charles Town (renamed Charleston in 1783) was the political, social, and economic heart of the center of South Carolina during the colonial and antebellum (pre-Civil War) eras and was the state capital until 1790.

Plantation life and high merchant activity made Charleston one of the busiest ports along the East Coast of the British colonies.

During the Revolutionary War, the soon-to-be American forces defeated the British fleet in the attack of Charleston in June 1776. Another victory against the British Army was when a palmetto tree log fort (later named Fort Moultrie) on Sullivan's Island withstood an intense barrage of British cannonballs.

Today the South Carolina flag features a palmetto tree. Charleston's place in American history will never be forgotten because of its role in the Civil War.

In April 1861, Fort Sumter a federal stronghold was fired upon by Confederate forces signaling the start of the Civil War.

- When you are finished touring, be sure to visit Ft. Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island north of the city.

- Charleston Museum, directly across from the Visitors Center on Meeting Street, has an outstanding display of colonial-era dishes, furniture, fabric, art, and militaria.

- The Charleston City Day Market, which is over 200 years old. It is open from 9:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. daily and features several hundred artists, craftspeople, and entrepreneurs.

Be sure to check out our pay-what-you-wish walking tours of Charleston and make the most of your time and money in this beautiful city.

RELATED POSTS