I’m Jessica the Museum Guide, and I love visiting museums around the world. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of the biggest and best, with a collection of over 2 million pieces of art and artifacts. It was at the top of my list when I visited New York, and I spent many hours here exploring the collection.

When you enter this museum, take a moment to really stop, breathe in, and get ready for the fantastic experience you are about to have. If you’re an art lover, an archeology lover, or just a lover of museums in general, you’re in for a treat.

But let’s be honest - it would take you weeks to really stop and admire every work on display. But what if you have just a few hours to visit The Met, like I did? Let me help you make the most of your visit. Here is a rundown of some of the must-see pieces that you shouldn’t miss.

My list of the most famous artwork at The Metropolitan Museum of Art should get you off to a good start. If I missed your favorite, head to our social media accounts and let me know!

- Famous Paintings At The Met

- Great Spaces In The Met

- How to Visit The Met

- Tips From Locals and Travelers

- Metropolitan Museum Tours

- Best Museums In New York City

Our list below of famous artwork at The Metropolitan Museum of Art should get you off to a good start.

The Death of Socrates, Jacques-Louis David, 1787

Gallery 614.

This Neoclassical work is one of the most famous paintings at The Met. David was a master of Academic Art in Paris – that is, art that was beloved by the Académie des Beaux Arts.

They ran annual salons (essentially art contests), and mythical subject matter was highly praised and decorated.

David’s work portrays the moments just before the death of the great philosopher Socrates, based on his student Plato’s record of the event.

At the time of his death by suicide, a tyrannical Athenian government was in power. Socrates’ teachings were deemed to be corrupting the young.

Socrates was put on trial and condemned for his beliefs – he was offered the option of renouncing his ideas or drinking poison. He chose the latter and died for his beliefs.

This masterpiece captures the sadness of Socrates’ followers contrasted with Socrates’s calm as he, according to Plato, “died nobly and without fear.”

The work is lifelike and idealized, stylistic choices that were praised in the Salons. David’s Neoclassicism would go on to influence painters throughout the 19th century - and to this day.

Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat, Vincent van Gogh, 1887

Gallery 825.

One of Van Gogh’s most famous paintings was completed during his stay with his brother Vincent in Paris from 1886-1888.

During these two years, Van Gogh produced more than 20 self-portraits, something he is still famous for today.

When short of funds and unable to hire a model, Van Gogh “purposely bought a good enough mirror to work from myself."

The short, sharp strokes capture something of the artist’s essence, while the somber look on his face is what I most associate with this tragic figure.

Vincent’s life story still brings a pang to my heart, and this painting has a yearning quality that continued to haunt me long after I left these hallowed halls.

Washington Crossing The Delaware, Emanuel Leutze, 1851

Gallery 760.

When you enter Gallery 760, be prepared to gasp. That’s because this painting stands out amongst the hundreds of paintings in The Met for its sheer size alone – I felt dwarfed by the canvas.

At 12.4 feet by 21.3 feet (3.8m by 6.5 m), it takes up a large portion of the wall upon which it hangs.

It’s not only epic in size but also in its historic significance.

The scene depicts the night of December 25, 1776, when General George Washington and the Continental Army crossed the Delaware River.

Washington launched a surprise attack on a Hessian military base where soldiers hired by the British were stationed.

Morale was low among the Continental Army, and Washington was determined to score a victory by the end of the year.

The mission’s success re-ignited the passion for the cause of the patriots. That’s why the painting is now an American icon.

I’m Canadian/British, but this painting is iconic even for me – no matter where you’re from, you’ll recognize it!

Bridge Over a Pond of Water Lilies, Claude Monet, 1899

Gallery 819.

In 1893, Monet, regarded as the father of Impressionism, purchased land near his property in Giverny, France.

The land included a pond he planned to turn into a “pleasure of the eye and also for motifs to paint.”

He succeeded splendidly as his pond inspired him to start a series of 18 views of the small footbridge over the pond.

The vertical format of the painting is unusual for the series. Monet chose this format to draw the viewer to the water lilies and their reflections in the water.

I’m used to viewing Monet in London and France, so seeing this unique painting here in New York was quite a treat, and it will be for you, as well.

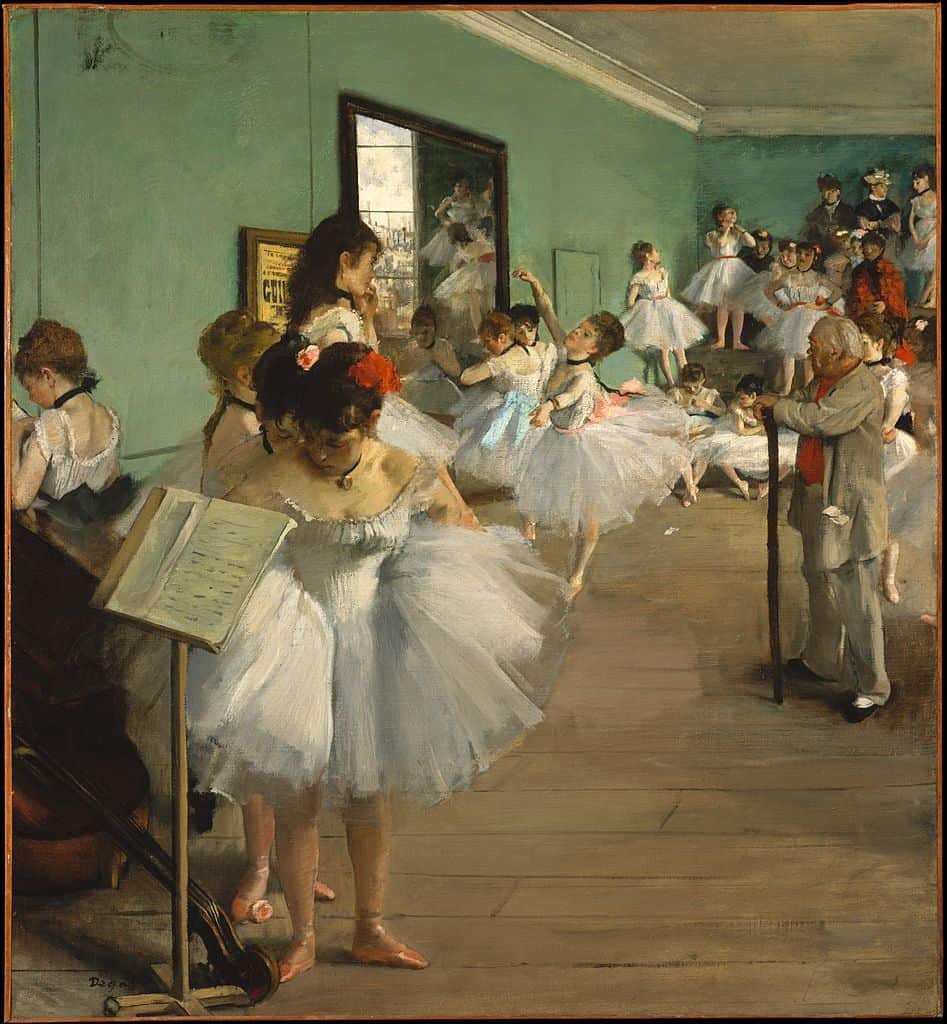

The Dance Class, Edgar Degas, 1874

Gallery 815.

Degas was one of the famed French Impressionist painters, right alongside Monet. He is known primarily for his dance-themed works, specifically young ballerinas.

His paintings don't portray innocence, however; I was shocked to learn that these young girls were actually forced into sex-work to pay their way through ballet school!

Degas was interested in the juxtaposition between the grace of the dance and the dark world of “les petits rats,” as the young ballerinas were called.

He painted over 600 ballet scenes, mainly rehearsals and backstage views. He was fascinated by movement as well as the atmosphere created by artificial, indoor light.

Degas said that the natural light favored by his peers was “too easy,” indirectly and controversially critiquing other Impressionist painters who favored outdoor settings.

Degas’s use of light can be compared with the next Met painting by Vermeer, often called the “master of light.”

Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, Johannes Vermeer, 1662

Gallery 630.

Let’s step back in time to the 17th century, when Dutch master Vermeer worked in the Baroque style.

It’s believed that in his life he painted approximately 45 works, which surprised me - for how famous he is, I would have expected many more.

There are only thirty-four Vermeer paintings that survive, and The Met has five of them, more than any other museum in the world (Three more are a few blocks away at The Frick Collection, which is very much worth your time as well!).

I felt really spoiled here, because we only have two at the National Gallery in London, where I live!

Painted early on in his career, and with no formal training, Vermeer came to master the depiction of light across different surfaces.

In this painting, daylight streams through the window and is reflected in the golden window frame.

The woman’s white bonnet is semi-translucent, catching the light in its folds. The light bounces off the metal pitcher and bowl which have reflections of the cloth underneath them.

These are such small details, but they really blow me away and demonstrate why Vermeer’s works are so revered today.

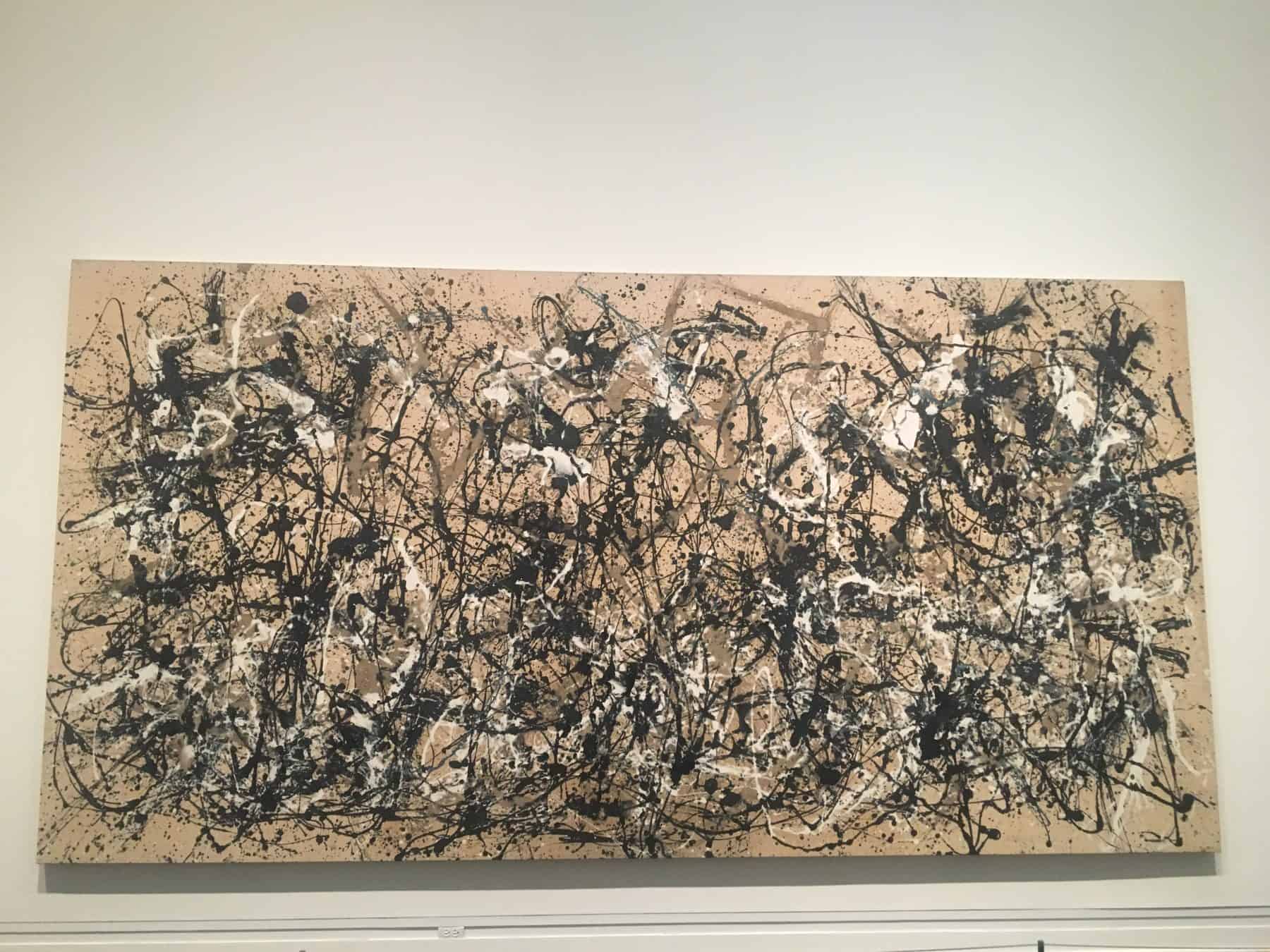

Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, Jackson Pollock, 1950

Gallery 919.

Now we’re talking – I love modern art! Jackson Pollock, one of the founders of the Abstract Expressionism movement, created this large canvas using his innovative poured-painting technique.

Pollock worked on the canvas while it lay flat on the floor, so he could move the canvas and apply the paint from all four sides.

This afforded him the freedom to use his technique of flicking, splattering, and dripping paint onto the canvas. Seeing this in person was such a treat for me!

The beauty of visiting The Met is having the opportunity to contrast works like this one with other dramatically different works, like Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, painted 300 years apart.

That really makes this such a special museum.

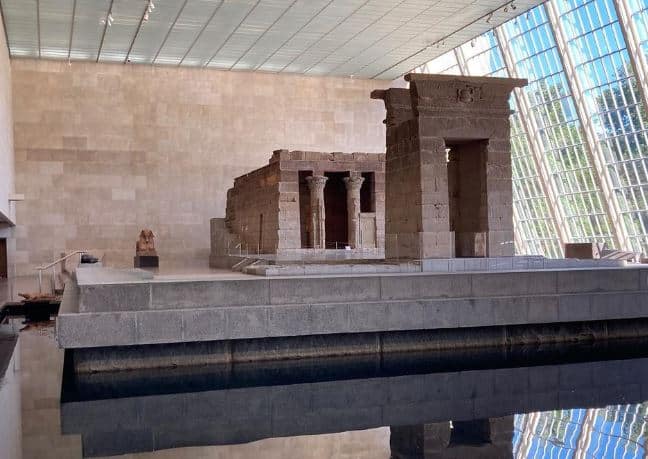

Temple of Dendur, c. 10 BC

Gallery 131.

Let’s step back into archaeological history with this Egyptian temple completed by 10 BC, was rebuilt from its original stones and blocks. Yes, this is antiquity and history, but it is also art.

I walked through the structure and was surprised that visitors are even encouraged to touch it – I felt transported back to Ancient Egypt.

The temple, dedicated to the goddess Isis, and the gods Harpocrates and Osiris, is really one of the gems of The Met.

Its splendor is enhanced by its placement in the incredible Sackler Wing in a manner that mimics its location in Egypt.

I was really impressed with this curation - the reflecting pool represents the Nile River and the sloping wall behind the temple represents the cliffs nearby.

The stippled glass wall diffuses the light to recreate the temple’s outdoor lighting. Shockingly, this temple was almost lost forever to flooding during the construction of the Aswan Dam.

However, UNESCO worked with Egypt to relocate this temple, and Egypt formally gifted it to the United States.

None other than Jacqueline Onassis helped New York and the Met secure the temple for display – others wanted to see it in DC.

Years later, her Fifth Avenue apartment window conveniently looked down on the glass atrium surrounding Temple of Dendur, and the museum left it lit at night as a thank you so she could admire it from the comfort of her home.

The Temple of Dendur is a ‘must-see’ at The Met.

A Human-Headed Winged Lion (lamassu), unknown sculptor, c. 883-859 BC

Gallery 401.

In the 9th century BC, the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II built a palace in Nimrud (today’s northern Iraq).

Guarding the entrance to the palace was this pair of lamassu, human-headed winged lions, representing a Sumerian female deity called Lama.

These powerful, menacing creatures supported the main doorways of many Assyrian palaces to protect the king from evil.

An interesting feature is the lamassu’s five legs, which gave the appearance of standing firmly upon approach but striding forward when viewed from the side.

When I guide these monuments, I love pointing this out to my guests – this is a very early form of depth and perspective in art.

The Sphinx of Hatshepsut, unknown sculptor, c. 1479-1458 BC

Gallery 131.

The female Egyptian Pharaoh Hatshepsut ruled in the 15th century BCE. Six granite sphinxes stood guard at her burial site to keep her safe through the ages.

However, her successor, Thutmose III, ordered that they be destroyed. Ultimately, fragments of this sphinx were gathered and reformed into this enormous sculpture.

This sphinx depicts Hatshepsut with the body of a lion and a human head wearing a nemes (traditional headcloth).

Unlike the most famous sphinx at the Pyramids of Giza, the Sphinx of Hatshepsut still has a nose!

All the famous art at The Met might not appear so spectacular if they were not curated in the manner they are. I really appreciate great curation, and the Met is some of the best in the entire world.

After all, great pieces of art deserve great spaces to be displayed. The Met does not fall short!

American Wing Court

The Charles Engelhard Court is an expansive light-filled space serving as the vestibule to the American Wing.

The glassed-in courtyard features stained-glass windows and large-scale American sculptures.

One end of the court is the actual Neoclassical facade of the Branch Bank of the United States, originally located on Wall Street.

When the bank was torn down, its facade was moved to the museum - it is so fascinating to see it here. Artefacts from great empires old and new, side by side.

This court is one of The Met’s most popular spaces to sit and relax. There is also a cafe if you want to grab some light fare.

European Sculpture Court

The light and airy Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court is filled with French and Italian works from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

The court is designed to look like a French garden and contains sculptures that were once displayed outdoors. This is such a pretty way to see these works displayed with an indoor/outdoor feel.

At the end of the court is a wall of windows facing Central Park.

Greek and Roman Art Court

The Met’s collection has more than 30,000 Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, objects, and artifacts that date from the Neolithic period (ca. 4500 B.C.) up to A.D. 312 when Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity.

This monumental collection deserves a monumental space to be seen, hence the creation of the Leon Levy and Shelby White Court in 2007. I had read about this court, and seeing it in person did not disappoint.

This huge peristyle court in a two-story skylit atrium is a "museum-within-the-museum" as impressive as the historic art and objects on display within.

The Cantor Roof Garden

Above the museum is this large rooftop garden with unrivalled views of Central Park and the surrounding buildings.

There are two bars on either end of the rooftop. Sometimes the roof garden will feature a contemporary art installation, and it is the perfect place for photos, as you can see below!

That’s me and my husband on a very hot day in Manhattan.

Hours are Sunday-Tuesday and Thursday 11 am to 4:15 pm, Friday and Saturday from 11 am to 4 pm, and again from 5 pm to 8:30 pm. Don't get caught out – it is closed Wednesday.

How To Visit The Met

For information on visiting The Metropolitan Museum of Art, read our in-depth post, Metropolitan Museum of Art Tickets, and watch the video below.

Tips From Locals and Travelers

While these are some of the more noteworthy and popular attractions in the Met, there's always a chance that we missed a few stand-out pieces in this massive museum.

Thankfully, we have a New York City Travel Tips group on Facebook where you can ask others about their favorite exhibits, and that's just what we did!

Here are a few of the more interesting responses we received.

The Temple of Dendur seems to be one of the more popular exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and several of our group members recommend checking it out.

The Egyptian art section, which includes The Sphinx of Hatshepsut, is another favorite among many art lovers who have wandered around this historic museum.

Some visitors also really enjoy the arms & armor collection at this museum, and it's not hard to see why, as it includes examples of armament from several different cultures spanning thousands of years of history.

Another popular option is the Unicorn Tapestries at the Cloisters in Gallery 17. Remember, admission to the main museum also covers admission to the Cloisters!

For even more excellent suggestions, consider asking our New York City Travel Tips Facebook Group for even more great artwork that you absolutely MUST see at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Related Posts